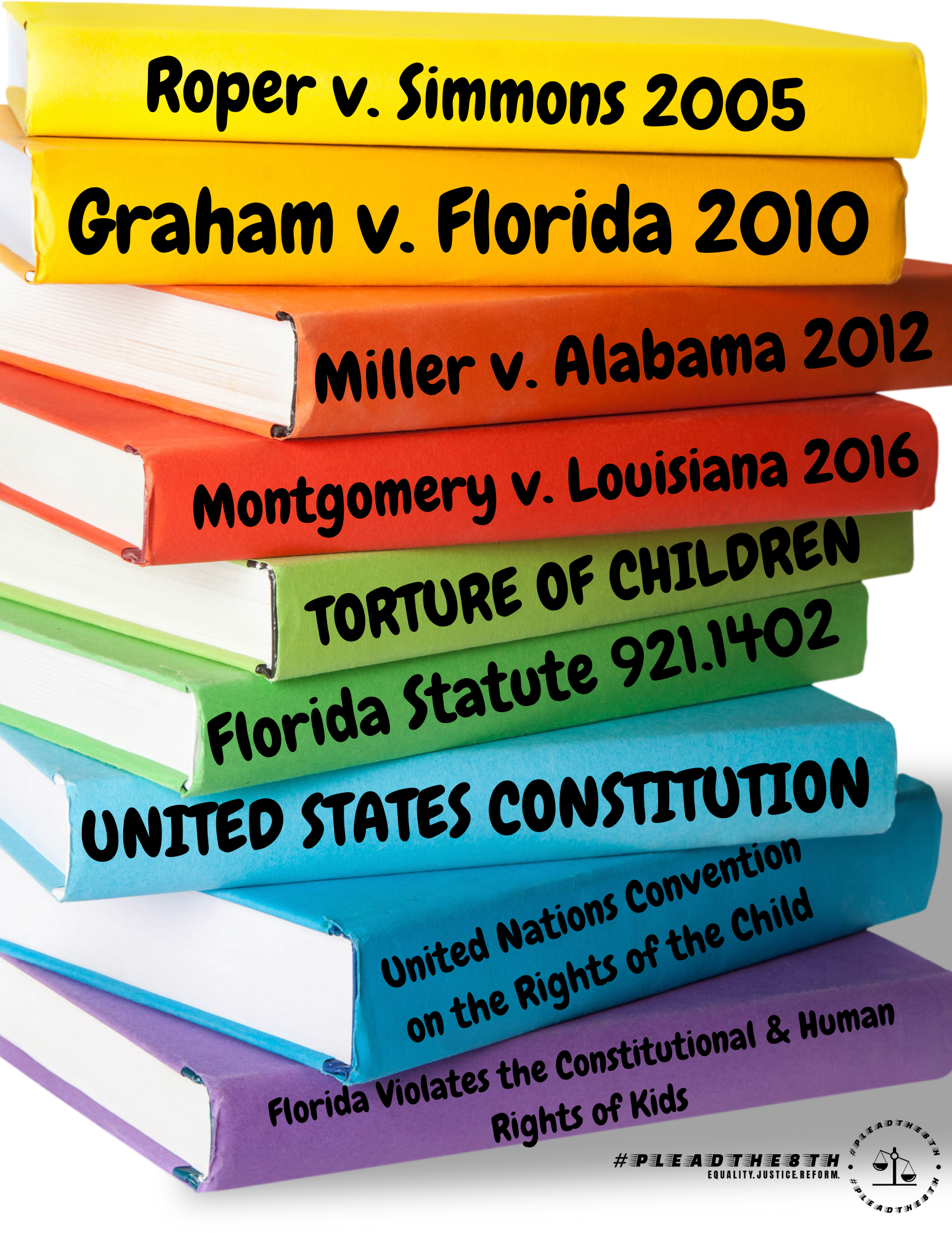

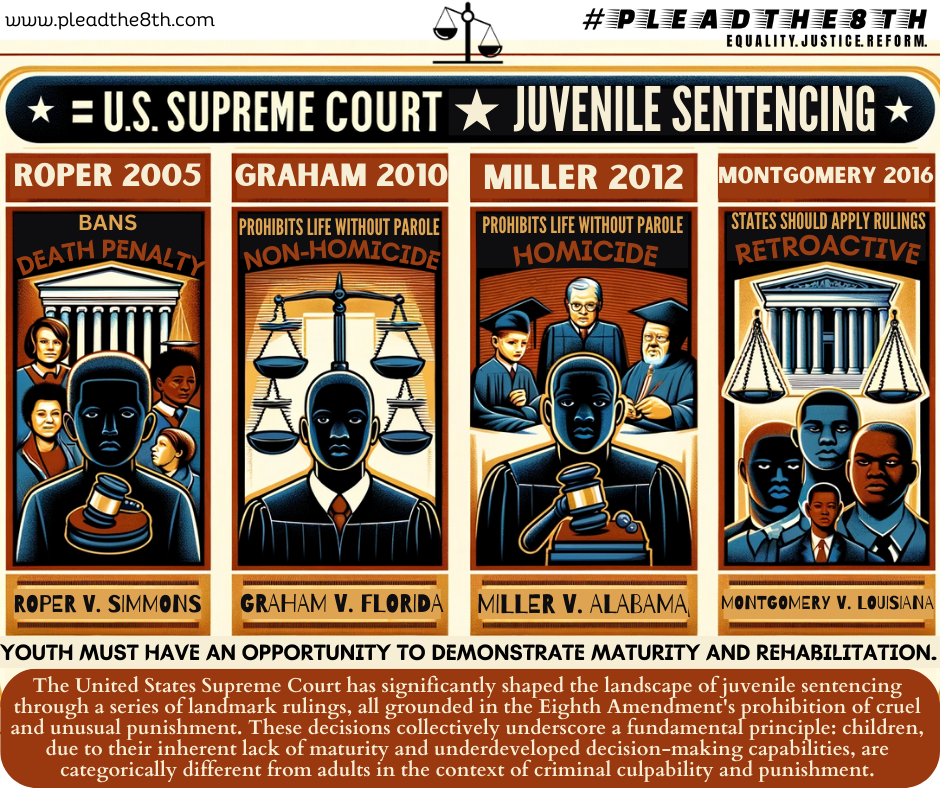

U.S. Supreme Court Precedents on Juvenile Sentencing

Review the critical precedents set by the U.S. Supreme Court that have shaped current juvenile sentencing guidelines and practices.

Roper

Graham

Miller

Montgomery

Over the past eighteen years, the United States Supreme Court has significantly shaped the landscape of juvenile sentencing through a series of landmark rulings, all grounded in the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment.

These decisions collectively underscore a fundamental principle: children, due to their inherent lack of maturity and underdeveloped decision-making capabilities, are categorically different from adults in the context of criminal culpability and punishment.

United States Supreme Court Cases on Juvenile Sentencing

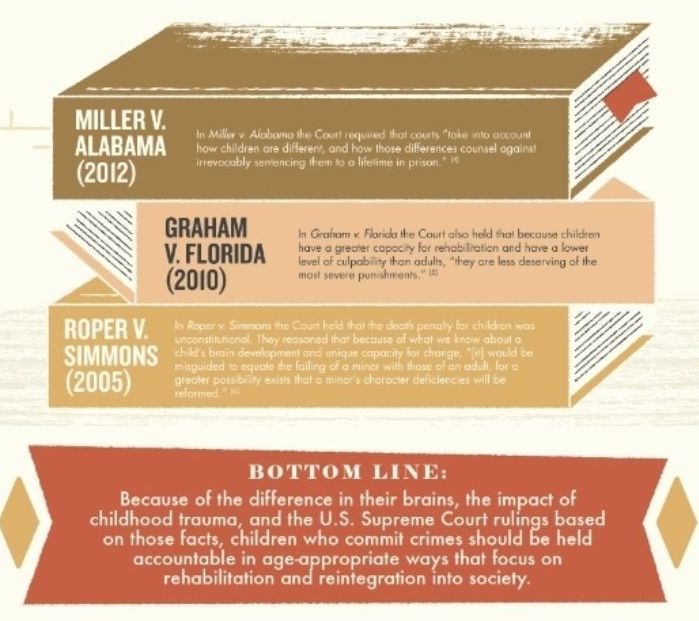

SCOTUS [2005]: Roper v. Simmons

Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005)

Docket No. 03-633

Granted: January 26, 2004

Argued: October 13, 2004

Decided: March 1, 2005

Listen: Oral Opinion Announcement

Question: Does the execution of minors violate the prohibition of "cruel and unusual punishment" found in the Eighth Amendment and applied to the states through the incorporation doctrine of the 14th Amendment?

Conclusion: Yes. In a 5-4 opinion delivered by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the Court ruled that standards of decency have evolved so that executing minors is "cruel and unusual punishment" prohibited by the Eighth Amendment.

Held: The Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments forbid imposition of the death penalty on offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed. Pp. 6–25.

Quotes from the Court:

"The Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments forbid imposition of the death penalty on offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed."

SCOTUS [2010]: Graham v. Florida

Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010)

Docket No. 08-7412

Granted: May 4, 2009

Argued: November 9, 2009

Decided: May 17, 2010

Listen: Oral Opinion Announcement

Question: Does the imposition of a life sentence without parole on a juvenile convicted of a non-homicidal offense violate the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of "cruel and unusual punishment?"

Conclusion: Yes. In a 6-3 decision,the Supreme Court held that the Eight Amendment's Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause does not permit a juvenile offender to be sentenced to life in prison without parole for a non-homicidal crime. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, writing for the majority, reasoned that because this case implicates a particular type of sentence as it applies to an entire class of offenders (juveniles), the categorical analysis under Atkins, Roper, and Kennedy governs. Under this approach, the Court must: (1) consider objective indicia of society's standards and (2) determine whether the punishment in question violates the Constitution guided by the standards elaborated by controlling precedents. Here, the Court concluded that both (1) and (2) indicated that the punishment in question for the class in question was unconstitutional. The Court made a point to note that life sentences for juveniles for non-homicidal crimes has been "rejected the world over."

On May 17, 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that life-without-parole sentences for juveniles convicted of nonhomicide offenses are unconstitutional.

Quotes from the Court:

- "The trial court found Graham guilty of the earlier armed burglary and attempted armed robbery charges. It sentenced him to the maximum sentence authorized by law on each charge: life imprisonment for the armed burglary and 15 years for the attempted armed robbery. "

- "Florida has abolished its parole system, see Fla. Stat. §921.002(1)(e) (2003), a life sentence gives a defendant no possibility of release unless he is granted executive clemency."

- "Under Florida law the minimum sentence Graham could receive absent a downward departure by the judge was 5 years’ imprisonment. The maximum was life imprisonment. Graham’s attorney requested the minimum nondeparture sentence of 5 years. A presentence report prepared by the Florida Department of Corrections recommended that Graham receive an even lower sentence—at most 4 years’ imprisonment. The State recommended that Graham receive 30 years on the armed burglary count and 15 years on the attempted armed robbery count."

- "A life without parole sentence improperly denies the juvenile offender a chance to demonstrate growth and maturity. Incapacitation cannot override all other considerations, lest the Eighth Amendment’s rule against disproportionate sentences be a nullity."

- "In sum, penological theory is not adequate to justify life without parole for juvenile nonhomicide offenders. This determination; the limited culpability of juvenile nonhomicide offenders; and the severity of life without parole sentences all lead to the conclusion that the sentencing practice under consideration is cruel and unusual. This Court now holds that for a juvenile offender who did not commit homicide the Eighth Amendment forbids the sentence of life without parole. This clear line is necessary to prevent the possibility that life without parole sentences will be imposed on juvenile nonhomicide offenders who are not sufficiently culpable to merit that punishment. Because “[t]he age of 18 is the point where society draws the line for many purposes between childhood and adulthood,” those who were below that age when the offense was committed may not be sentenced to life without parole for a nonhomicide crime. Roper, 543 U. S., at 574."

- "To determine whether a punishment is cruel and unusual, courts must look beyond historical conceptions to “ ‘the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.’ ” Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U. S. 97, 102 (1976) (quoting Trop v. Dulles, 356 U. S. 86, 101 (1958) (plurality opinion)). “This is because ‘[t]he standard of extreme cruelty is not merely descriptive, but necessarily embodies a moral judgment. The standard itself remains the same, but its applicability must change as the basic mores of society change.’ ”

- "The Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause prohibits the imposition of inherently barbaric punishments under all circumstances. See, e.g., Hope v. Pelzer, 536 U. S. 730 (2002). “[P]unishments of torture,” for example, “are forbidden.”" Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U. S. 130, 136 (1879).

- "The concept of proportionality is central to the Eighth Amendment. Embodied in the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishments is the “precept of justice that punishment for crime should be graduated and proportioned to [the] offense.” Weems v. United States, 217 U. S. 349, 367 (1910)."

- "Roper established that because juveniles have lessened culpability they are less deserving of the most severe punishments. 543 U. S., at 569. As compared to adults, juveniles have a “ ‘lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility’ ”; they “are more vulnerable or susceptible to negative influences and outside pressures, including peer pressure”; and their characters are “not as well formed.” Id., at 569–570."

- "Accordingly, “juvenile offenders cannot with reliability be classified among the worst offenders.” Id., at 569. A juvenile is not absolved of responsibility for his actions, but his transgression “is not as morally reprehensible as that of an adult.” Thompson, supra, at 835 (plurality opinion)."

- "It remains true that “[f]rom a moral standpoint it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult, for a greater possibility exists that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.”"

- "It follows that, when compared to an adult murderer, a juvenile offender who did not kill or intend to kill has a twice diminished moral culpability."

- "What the State must do, however, is give defendants like Graham some meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation."

SCOTUS [2012]: Miller v. Alabama

Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460 (2012)

Docket No. 10-9646

Granted: November 7, 2011

Argued: March 20, 2012

Decided: June 25, 2012

Listen: Oral Opinion Announcement

Question: Does the imposition of a life-without-parole sentence on a fourteen-year-old child violate the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments' prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment?

Conclusion: Yes. Writing for a 5-4 majority, Justice Elena Kagan reversed the Arkansas and Alabama Supreme Courts' decisions and remanded. The Court held that the Eighth Amendment's prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment forbids the mandatory sentencing of life in prison without the possibility of parole for juvenile homicide offenders. Children are constitutionally different from adults for sentencing purposes. While a mandatory life sentence for adults does not violate the Eighth Amendment, such a sentence would be an unconstitutionally disproportionate punishment for children.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer filed a concurring opinion. He argued for an additional determination that the offender actually killed or intended to kill the robbery victim. Without such a determination, the State could not pursue a mandatory life sentence. Justice Sonia Sotomayor joined in the concurrence.

- The Eighth Amendment forbids a sentencing scheme that mandates life in prison without the possibility of parole for juvenile homicide offenders.

- Children are constitutionally different from adults for sentencing purposes. Their lack of maturity and underdeveloped sense of responsibility lead to recklessness, impulsiveness, and heedless risk-taking. They are more vulnerable to negative influences and lack ability to extricate themselves from horrific, crime-producing settings.

- A child’s actions are less likely to be evidence of irretrievable depravity. The mandatory penalty schemes at issue prevent the sentencing court from considering youth and from assessing whether the harshest term of imprisonment proportionately punishes a juvenile offender.

- Life-without-parole sentences share characteristics with death sentences, demanding individualized sentencing. The Court rejected the states’ argument that courts and prosecutors sufficiently consider a juvenile defendant’s age, background and the circumstances of his crime, when deciding whether to try him as an adult. The argument ignores that many states use mandatory transfer systems or lodge the decision in the hands of the prosecutors, rather than courts.

SCOTUS [2016]: Montgomery v. Louisiana

Montgomery v. Louisiana, 577 U.S. 190 (2016)

Docket No.14-280

Granted: March 23, 2015

Argued: October 13, 2015

Decided: January 25, 2016

Listen: Oral Opinion Annoucement

Question:

1) Does the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Miller v. Alabama, which held that the Eighth Amendment prohibits mandatory sentencing schemes that require children convicted of homicide to be sentenced to life in prison without parole, apply retroactively?

(2)Does the U.S. Supreme Court have the jurisdiction to review the Louisiana Supreme Court’s determination that the Miller rule does not apply retroactively?

Conclusion: The Supreme Court had jurisdiction to review the Louisiana Supreme Court’s decision, and the Supreme Court’s decision in Miller v. Alabama, which prohibits sentencing schemes that impose a punishment of mandatory life without parole for juvenile offenders convicted of homicide, applied retroactively.

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy delivered the opinion for the 6-3 majority. The Court held that, when the Court establishes a substantive constitutional rule, that rule must apply retroactively because such a rule provides for constitutional rights that go beyond procedural guarantees. When a state court fails to give effect to a substantive rule, that decision is reviewable because failure to apply a substantive rule always results in the violation of a constitutional right, while failure to apply a procedural rule might or might not result in an illegitimate verdict. The Court held that Miller established a substantive rule because it prohibited the imposition of a sentence of life without parole for juvenile offenders. The Court’s analysis in that case was based on precedent that established that the Constitution treats children as different from adults for the purposes of sentencing. Therefore, the rule the Court announced in Miller made life without parole an unconstitutional punishment for a class of defendants based on their status as juveniles, and such a rule is substantive rather than procedural.

Quotes from the Court:

- "This is another case in a series of decisions involving the sentencing of offenders who were juveniles when their crimes were committed. In Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. ––––, 132 S.Ct. 2455, 183 L.Ed.2d 407 (2012), the Court held that a juvenile convicted of a homicide offense could not be sentenced to life in prison without parole absent consideration of the juvenile's special circumstances in light of the principles and purposes of juvenile sentencing. In the wake of Miller , the question has arisen whether its holding is retroactive to juvenile offenders whose convictions and sentences were final when Miller was decided. Courts have reached different conclusions on this point."

- "The Court now holds that Miller announced a substantive rule of constitutional law. The conclusion that Miller states a substantive rule comports with the principles that informed Teague . Teague sought to balance the important goals of finality and comity with the liberty interests of those imprisoned pursuant to rules later deemed unconstitutional. Miller 's conclusion that the sentence of life without parole is disproportionate for the vast majority of juvenile offenders raises a grave risk that many are being held in violation of the Constitution."

- "Giving Miller retroactive effect, moreover, does not require States to relitigate sentences, let alone convictions, in every case where a juvenile offender received mandatory life without parole. A State may remedy a Miller violation by permitting juvenile homicide offenders to be considered for parole, rather than by resentencing them. See, e.g., Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 6–10–301(c) (2013) (juvenile homicide offenders eligible for parole after 25 years). Allowing those offenders to be considered for parole ensures that juveniles whose crimes reflected only transient immaturity—and who have since matured—will not be forced to serve a disproportionate sentence in violation of the Eighth Amendment."

- "Extending parole eligibility to juvenile offenders does not impose an onerous burden on the States, nor does it disturb the finality of state convictions. Those prisoners who have shown an inability to reform will continue to serve life sentences. The opportunity for release will be afforded to those who demonstrate the truth of Miller 's central intuition—that children who commit even heinous crimes are capable of change."

SCOTUS [2020]: Jones v. Mississippi

Jones v. Mississippi, 593 U.S. ___ (2021)

Docket No. 18-1259

Granted: March 9, 2020

Argued: November 3, 2020

Decided: April 22, 2021

Listen: Oral Opinion Announcement

Question: Does the Eighth Amendment require a sentencing authority to find that a juvenile is permanently incorrigible before it may impose a sentence of life without the possibility of parole?

Conclusion: A sentencing authority need not find a juvenile is permanently incorrigible before imposing a sentence of life without the possibility of parole; a discretionary sentencing system is both constitutionally necessary and constitutionally sufficient to impose a sentence of life without parole on a defendant who committed a homicide when they were under 18. Justice Brett Kavanaugh authored the 6-3 majority opinion.

In Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460 (2012), the Court held that “a sentencer [must] follow a certain process—considering an offender’s youth and attendant characteristics—before imposing” a life-without-parole sentence.” And in Montgomery v. Louisiana, 577 U.S. 190 (2016), the Court stated that “a finding of fact regarding a child’s incorrigibility . . . is not required.” Taken together, these two cases refute Jones’s argument that a finding of permanent incorrigibility is constitutionally necessary to impose a sentence of life without parole. The Court noted that it expresses neither agreement nor disagreement with Jones’s sentence, and its decision does not preclude states from imposing additional sentencing limits in cases involving juvenile commission of homicide.

Justice Clarence Thomas authored an opinion concurring in the judgment, arguing that the Court should have reached the same outcome by declaring that Montgomery was incorrectly decided.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor authored a dissenting opinion, in which Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan joined. Justice Sotomayor argued that the majority effectively circumvents stare decisis by reading Miller to require only “a discretionary sentencing procedure where youth is considered.” Under Montgomery, sentencing discretion is necessary, but under Miller, it is not sufficient. Rather, a sentencer must actually make the judgment that the juvenile is one of those rare children for whom life without parole is a constitutionally permissible sentence.

Held: A sentencing authority need not find a juvenile is permanently incorrigible before imposing a sentence of life without the possibility of parole.

Quotes from the Court:

- "In the case of a defendant who committed a homicide when he or she was under 18, Miller and Montgomery do not require the sentencer to make a separate factual finding of permanent incorrigibility before sentencing the defendant to life without parole. In such a case, a discretionary sentencing system is both constitutionally necessary and constitutionally sufficient."

- "A sentencer need not make a separate factual finding of permanent incorrigibility before sentencing a murderer under 18 to life without parole. In Miller, the Court mandated “only that a sentencer followa certain process—considering an offender’s youth and attendant characteristics—before imposing” a life-without-parole sentence. 567 U. S., at 483. And in Montgomery, the Court stated that “a finding of fact regarding a child’s incorrigibility . . . is not required.” 577 U. S., at 211. Miller and Montgomery require consideration of an offender’s youth but not any particular factual finding. Miller and Montgomery therefore refute Jones’s argument that a finding of permanent incorrigibility is constitutionally necessary. Pp. 5–14. "

- "(2) Nor must a sentencer provide an on-the-record sentencing explanation with an “implicit finding” of permanent incorrigibility before sentencing a murderer under 18 to life without parole. An on-the-record sentencing explanation is not necessary to ensure that a sentencer considers a defendant’s youth. Nor is an on-the-record sentencing explanation required by or consistent with Miller or Montgomery, neither of which said anything about a sentencing explanation. Pp. 14–19. "

- "(3) The Court’s decision does not disturb Miller’s holding (that a State may not impose a mandatory life-without-parole sentence on a murderer under 18) or Montgomery’s holding (that Miller applies retroactively on collateral review). The resentencing in Jones’s case complied with Miller and Montgomery because the sentencer had discretion to impose a sentence less than life without parole in light of Jones’s youth. The Court’s decision today should not be construed as agreement or disagreement with Jones’s sentence. In addition, the Court’s decision does not preclude the States from imposing additional sentencing limits in cases involving murderers under 18. Nor does the Court’s decision prohibit Jones from presenting his moral and policy arguments against his life-without-parole sentence to the state officials who are authorized to act on those arguments."

Further analysis of the oral argument available at Oral Argument 2.0: https://argument2.oyez.org/2020/jones-v-mississippi/

KEY QUOTES FROM THE US SUPREME COURT ON JUVENILE SENTENCING

"To determine whether a punishment is cruel or unusual, the courts must look beyond historical conceptions to the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society."

To determine whether a punishment is cruel or unusual, the courts must look beyond historical conceptions to the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.

GRAHAM V. FLORIDA

"This Court's precedents establish that the Eighth Amendment forbids the imposition of otherwise permissible punishments when they are disproportionate to the offense or to the offender's culpability."

GRAHAM V. FLORIDA | ORAL ANNOUNCEMENT

"It is also well settled that the defendants who do not kill or intend to kill are less deserving of the most severe penalties. It follows that when compared to an adult murderer a juvenile offender who did not kill or intend to kill has a twice diminished moral culpability."

GRAHAM V. FLORIDA

"The state need not guarantee eventual freedom to juveniles convicted of non-homicide crimes, but it must give them some meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation."

Write your caption hereGRAHAM V. FLORIDA

"The concept of cruelty is not merely descriptive, it necessarily embodies a moral judgment."

Write your caption hereGRAHAM V. FLORIDA