Court Decisions on Florida Statute 921.1402

Over the past decade, Florida's §921.1402, a statute enacted in 2014 in response to landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions in Graham v. Florida (2010) and Miller v. Alabama (2012) on juvenile sentencing, has been mired in ambiguity and inconsistent application. As of 2023, there are over 32,000 incarcerated since childhood nationwide, while Florida holds the number 3 spot in the country with over 2,600.

This section provides an overview and details how various Florida courts have dealt with the statute, showcasing the outcomes and the judicial reasoning behind each decision.

OVERVIEW.

Youth, the US Supreme Court, & Florida confusion.

-

U.S. SUPREME COURT RULINGS

History of United States Supreme Court Rulings for Juvenile Offenders

The Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution states:

"Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted."

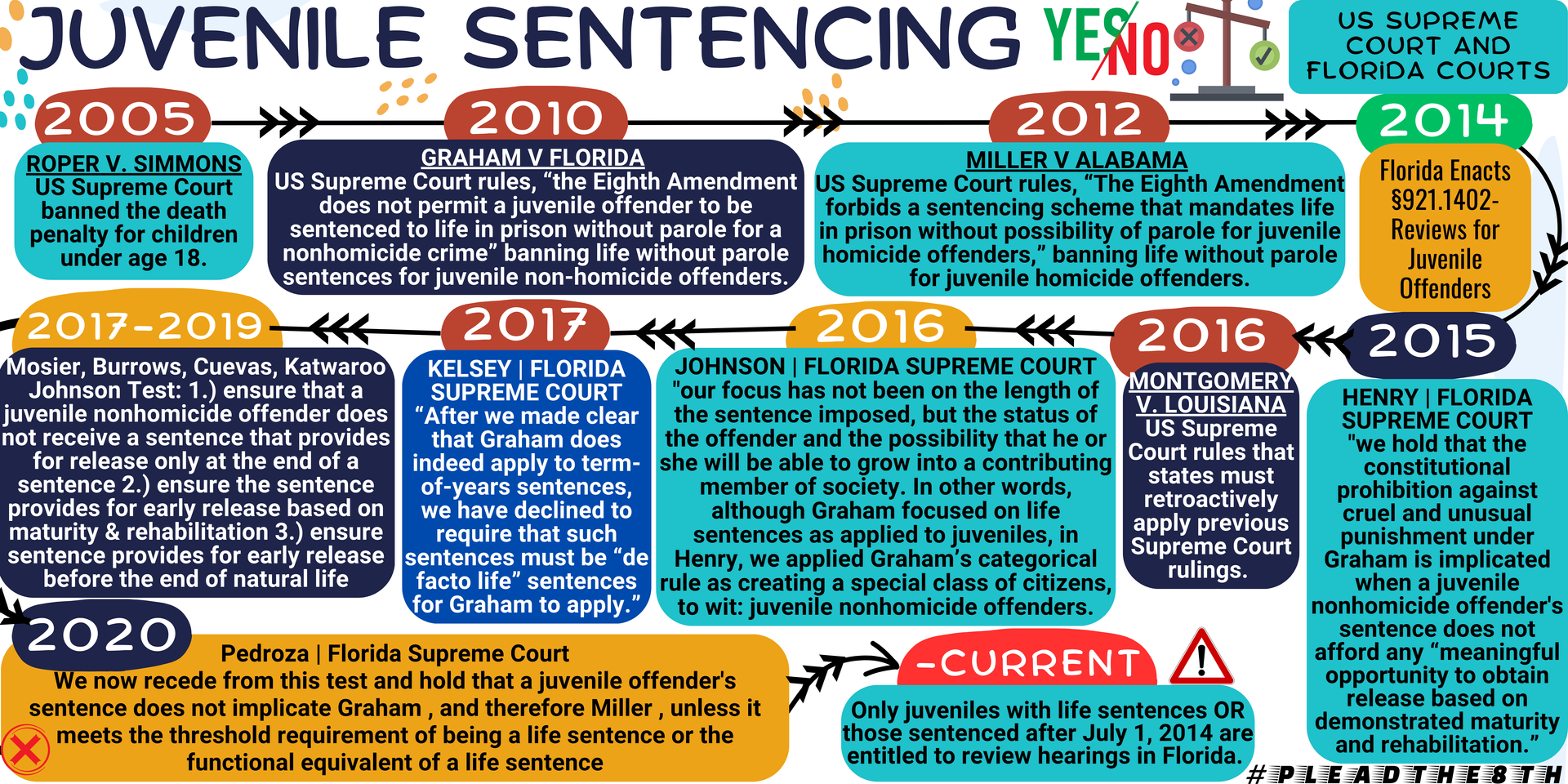

Over the past eighteen years, the United States Supreme Court has significantly shaped the landscape of juvenile sentencing through a series of landmark rulings, all grounded in the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment.

These decisions collectively underscore a fundamental principle: children, due to their inherent lack of maturity and underdeveloped decision-making capabilities, are categorically different from adults in the context of criminal culpability and punishment.

- 2005 | Roper v. Simmons | In Roper v. Simmons, the Court banned the death penalty for children under the age of 18.

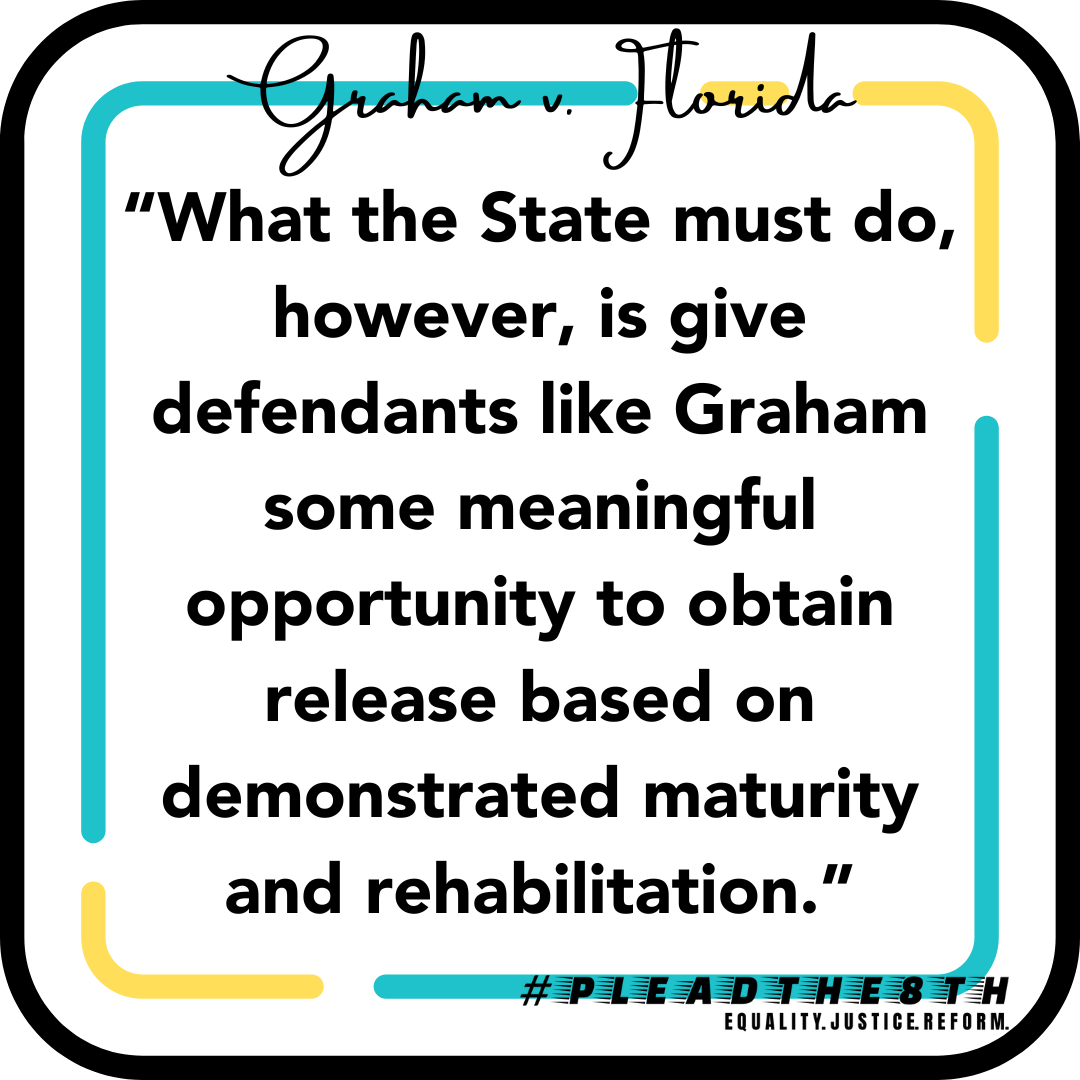

- 2010 | Graham v. Florida | The US Supreme Court held in Graham v Florida that “the Eighth Amendment does not permit a juvenile offender to be sentenced to life in prison without parole for a nonhomicide crime” banning life without parole sentences for juvenile non-homicide offenders. It emphasized the need for sentencing practices that consider the unique characteristics and potential for change in juveniles.

- 2012 | Miller v. Alabama | The US Supreme Court held in Miller v Alabama that, “The Eighth Amendment forbids a sentencing scheme that mandates life in prison without possibility of parole for juvenile homicide offenders” banning life without parole for juvenile homicide offenders. It mandated individualized sentencing considerations for juveniles, taking into account their age, circumstances, and potential for rehabilitation.

- 2016 | Montgomery v. Louisiana | The US Supreme Court held in Montgomery v. Louisiana that, “Miller is retroactive because it ‘necessarily carr[ies] a significant risk that a defendant’—here, the vast majority of juvenile offenders— ‘faces a punishment that the law cannot impose upon him.’ This ruling made the Miller decision retroactive, allowing individuals sentenced to life without parole as juveniles to seek resentencing or parole.

-

FLORIDA 2014

2014: Florida's Response to US Supreme Court Rulings

In 2014, Florida responded to the pivotal United States Supreme Court decisions concerning juvenile sentencing mentioned above by enacting §921.1402.

This statute specifically addresses the review of sentences for individuals convicted of offenses committed as juveniles.

Title XLVII CRIMINAL PROCEDURE AND CORRECTIONS Chapter 921 SENTENCE SECTION 1402

Review of sentences for persons convicted of specified offenses committed while under the age of 18 years.

921.1402 Review of sentences for persons convicted of specified offenses committed while under the age of 18 years.—

(1) For purposes of this section, the term “juvenile offender” means a person sentenced to imprisonment in the custody of the Department of Corrections for an offense committed on or after July 1, 2014, and committed before he or she attained 18 years of age.

(2)(a) A juvenile offender sentenced under s. 775.082(1)(b)1. is entitled to a review of his or her sentence after 25 years. However, a juvenile offender is not entitled to review if he or she has previously been convicted of one of the following offenses, or conspiracy to commit one of the following offenses, if the offense for which the person was previously convicted was part of a separate criminal transaction or episode than that which resulted in the sentence under s. 775.082(1)(b)1.:

1. Murder;

2. Manslaughter;

3. Sexual battery;

4. Armed burglary;

5. Armed robbery;

6. Armed carjacking;

7. Home-invasion robbery;

8. Human trafficking for commercial sexual activity with a child under 18 years of age;

9. False imprisonment under s. 787.02(3)(a); or

10. Kidnapping.

(b) A juvenile offender sentenced to a term of more than 25 years under s. 775.082(3)(a)5.a. or s. 775.082(3)(b)2.a. is entitled to a review of his or her sentence after 25 years.

(c) A juvenile offender sentenced to a term of more than 15 years under s. 775.082(1)(b)2., s. 775.082(3)(a)5.b., or s. 775.082(3)(b)2.b. is entitled to a review of his or her sentence after 15 years.

(d) A juvenile offender sentenced to a term of 20 years or more under s. 775.082(3)(c) is entitled to a review of his or her sentence after 20 years. If the juvenile offender is not resentenced at the initial review hearing, he or she is eligible for one subsequent review hearing 10 years after the initial review hearing.

(3) The Department of Corrections shall notify a juvenile offender of his or her eligibility to request a sentence review hearing 18 months before the juvenile offender is entitled to a sentence review hearing under this section.

(4) A juvenile offender seeking sentence review pursuant to subsection (2) must submit an application to the court of original jurisdiction requesting that a sentence review hearing be held. The juvenile offender must submit a new application to the court of original jurisdiction to request subsequent sentence review hearings pursuant to paragraph (2)(d). The sentencing court shall retain original jurisdiction for the duration of the sentence for this purpose.

(5) A juvenile offender who is eligible for a sentence review hearing under this section is entitled to be represented by counsel, and the court shall appoint a public defender to represent the juvenile offender if the juvenile offender cannot afford an attorney.

(6) Upon receiving an application from an eligible juvenile offender, the court of original sentencing jurisdiction shall hold a sentence review hearing to determine whether the juvenile offender’s sentence should be modified. When determining if it is appropriate to modify the juvenile offender’s sentence, the court shall consider any factor it deems appropriate, including all of the following:

(a) Whether the juvenile offender demonstrates maturity and rehabilitation.

(b) Whether the juvenile offender remains at the same level of risk to society as he or she did at the time of the initial sentencing.

(c) The opinion of the victim or the victim’s next of kin. The absence of the victim or the victim’s next of kin from the sentence review hearing may not be a factor in the determination of the court under this section. The court shall permit the victim or victim’s next of kin to be heard, in person, in writing, or by electronic means. If the victim or the victim’s next of kin chooses not to participate in the hearing, the court may consider previous statements made by the victim or the victim’s next of kin during the trial, initial sentencing phase, or subsequent sentencing review hearings.

(d) Whether the juvenile offender was a relatively minor participant in the criminal offense or acted under extreme duress or the domination of another person.

(e) Whether the juvenile offender has shown sincere and sustained remorse for the criminal offense.

(f) Whether the juvenile offender’s age, maturity, and psychological development at the time of the offense affected his or her behavior.

(g) Whether the juvenile offender has successfully obtained a high school equivalency diploma or completed another educational, technical, work, vocational, or self-rehabilitation program, if such a program is available.

(h) Whether the juvenile offender was a victim of sexual, physical, or emotional abuse before he or she committed the offense.

(i) The results of any mental health assessment, risk assessment, or evaluation of the juvenile offender as to rehabilitation.

(7) If the court determines at a sentence review hearing that the juvenile offender has been rehabilitated and is reasonably believed to be fit to reenter society, the court shall modify the sentence and impose a term of probation of at least 5 years. If the court determines that the juvenile offender has not demonstrated rehabilitation or is not fit to reenter society, the court shall issue a written order stating the reasons why the sentence is not being modified.

▶ FOR OVER A DECADE, THE COURTS HAVE REPEATEDLY URGED THE LEGISLATURE TO ADDRESS THE CRITICAL ISSUES IN §921.1402, HIGHLIGHTING AN URGENT NEED FOR CLARITY AND REFORM TO ENSURE JUSTICE AND FAIRNESS FOR YOUTH.

-

FLORIDA 2015 - 2019

2015-2020: A Period of Hope and Uncertainty

From 2015 to 2020, Florida's juvenile justice system saw a series of legal shifts and clarifications, in response to the U.S. Supreme Court's decisions in Graham v. Florida and Miller v. Alabama. These rulings catalyzed changes in how juvenile offenders were sentenced, especially those serving life sentences or lengthy terms of years.

The state's response, through §921.1402, aimed to provide a pathway for review and possible early release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation. However, the period was marked by significant ambiguity and inconsistency in the law's application. Courts frequently grappled with the statute's scope and intent, leading to a patchwork of interpretations and outcomes.

Juvenile offenders found themselves navigating a complex and often uncertain legal landscape, resulting in inequitable treatment of youth throughout the state of Florida.

From 2016-2019, numerous incarcerated juveniles, with both life and term-of-year sentences, were granted judicial reviews and resentencing throughout the state of Florida, due to Florida Supreme Court cases Henry, Kelsey, and Johnson which collectively stated, "all juveniles are entitled to sentencing reviews."

-

FLORIDA 2020 - CURRENT

2020-Current: The Shift and Continued Struggle for Clarity

The year 2020 marked a turning point with the Pedroza v. State decision, which significantly narrowed the scope of juveniles eligible for sentencing reviews under §921.1402. This shift left many juveniles, particularly those with long-term term-of-years sentences, without the prospect of a review. This decision contradicted earlier understandings of the law's breadth and intent.

The current period continues to be defined by efforts to address these narrowed interpretations and the ongoing disparities in pre-and post-2014 cases. Legislative reforms to rectify the inequities and ensure that all juveniles have a fair chance at rehabilitation are vital.

- In the case of Pedroza, the Florida Supreme Court rules that retroactivity only pertains to juveniles that were sentenced to life.

"While the foregoing conclusions resolve the narrow issue presented in this case, we recognize that there has understandably been "considerable confusion" in the district courts of this state—caused largely by confusing language and dicta in our prior decisions—as to when a juvenile offender's term-of-years sentence requires resentencing under Miller or Graham ."

- This ruling no longer allows juveniles with term of years sentences before July 1, 2014, to obtain a review hearing.

- This ruling contradicts the previous ruling that it was unconstitutional to sentence a child to prison without a review mechanism regardless of length of sentence.

- CURRENTLY IN FLORIDA: Only kids with Life sentences or those who committed crimes after July 1, 2014 are entitled to reviews.

- Kids sentenced as adults with TERM OF YEARS sentences BEFORE July 1, 2014, are being denied reviews, while those AFTER the effective date are entitled to reviews.

Youth in Florida Courts

(2015-2019) = Reviews for All Kids

-

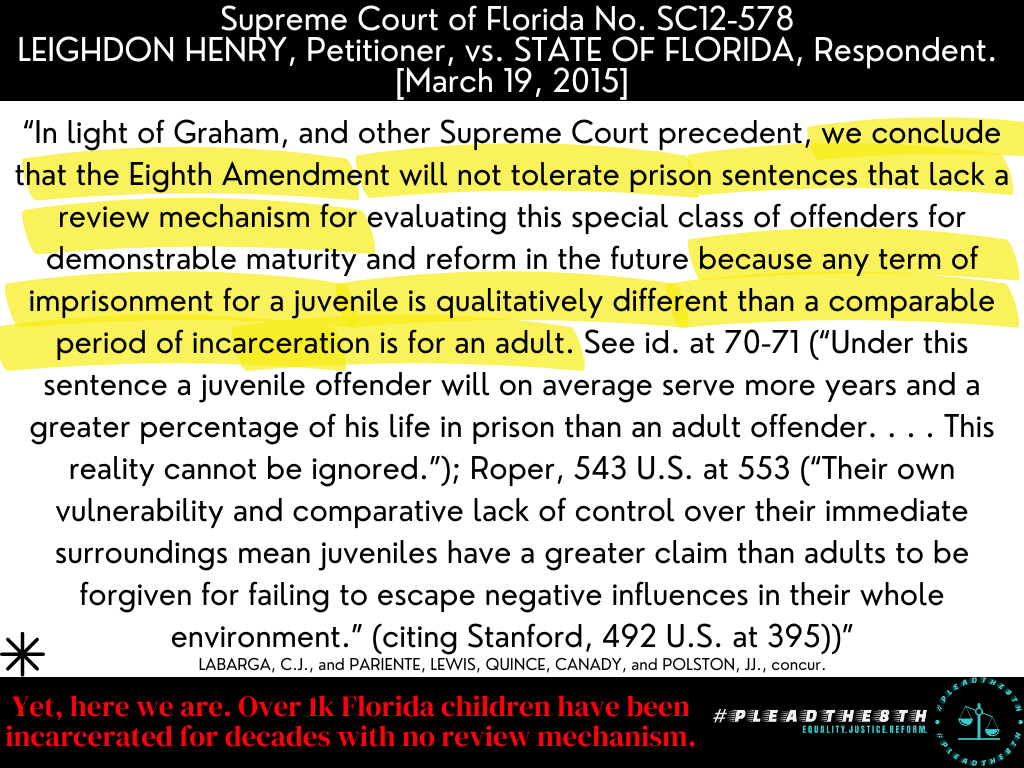

HENRY | 3/19/2015 | Florida Supreme Court

"we hold that the constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment under Graham is implicated when a juvenile nonhomicide offender's sentence does not afford any “meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.” Graham, 560 U.S. at 75, 130 S.Ct. 2011. Graham requires a juvenile nonhomicide offender, such as Henry, to be afforded such an opportunity during his or her natural life. Id. Because Henry's aggregate sentence, which totals ninety years and requires him to be imprisoned until he is at least nearly ninety-five years old, does not afford him this opportunity, that sentence is unconstitutional under Graham."

-

Gridine | 3/19/2015 | Florida Supreme Court

This case is before the Court for review of the decision of the First District Court of Appeal in Gridine v. State, 93 So.3d 360 (Fla. 1st DCA 2012). In its decision, the district court certified the following question as one of great public importance:

"DOES THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT DECISION IN GRAHAM V. FLORIDA, 560 U.S. 48, 130 S.Ct. 2011, 176 L.Ed.2d 825 (2010), PROHIBIT SENTENCING A FOURTEEN–YEAR–OLD TO A PRISON SENTENCE OF SEVENTY YEARS FOR THE CRIME OF ATTEMPTED FIRST–DEGREE MURDER?"

For the reasons that we explained in Henry v. State, 175 So.3d 675, 679– 80, No. SC12-578, 2015 WL 1239696 (Fla.2015) we determine that the seventy-year prison sentence of this juvenile nonhomicide offender does not provide a meaningful opportunity for future release. Therefore, Gridine's prison sentence is unconstitutional in light of Graham. Accordingly, we answer the certified question in the affirmative, quash the decision on review, and remand this case to Gridine's sentencing court.

-

Kelsey | 12/8/2016 | Florida Supreme Court

Kelsey | Florida Supreme Court | 12/8/2016

The following question was certified by the First District: Whether a defendant whose initial sentence for a nonhomicide crime violates Graham v. Florida, and who is resentenced to concurrent forty-five year terms, is entitled to a new resentencing under the framework established in chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida?

Is a defendant whose original sentence violated Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010), and who was subsequently resentenced prior to July 1, 2014, entitled to be resentenced pursuant to the provisions of chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida?

After we made clear that Graham does indeed apply to term-of-years sentences, we have declined to require that such sentences must be “de facto life” sentences for Graham to apply.

Holding that a juvenile's concurrent forty-five-year sentences were unconstitutional "not because of the length of his sentence, but because it did not provide him a meaningful opportunity for early release" during his natural life

-

Tarrand | 9/2/2016 | DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL FLORIDA FIFTH DISTRICT

Tarrand | 9/2/2016 | DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA FIFTH DISTRICT

"Admittedly, this case is different because it involves a homicide. Nonetheless, we believe our supreme court intends to apply the holdings of Henry and Gridine to juvenile homicide offenders who receive lengthy term-of-years sentences. We reach that conclusion based on the Florida Supreme Court's decision in Thomas v. State, 177 So.3d 1275 (Fla.2015), which quashed the underlying decision approving a juvenile homicide defendant's forty-year prison sentence. The supreme court ordered the juvenile to be resentenced in conformance with the 2014 juvenile sentencing statutes.

Thus, we hold that while Tarrand's initial sentence was not prohibited under the Eighth Amendment, he must be resentenced in light of the new juvenile sentencing legislation now codified at sections 775.082, 921.1401 and 921.1402, Florida Statutes, to allow him a meaningful opportunity to obtain early release based upon demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.

REVERSED FOR RESENTENCING."

-

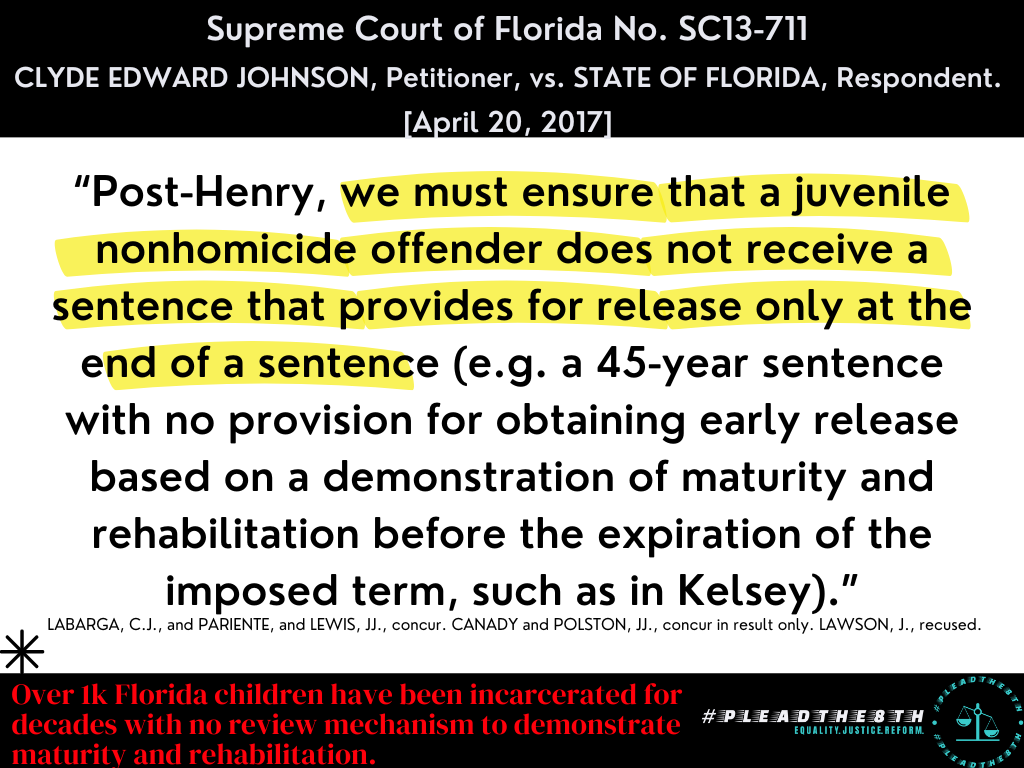

Johnson | 4/20/2017 | FLORIDA SUPREME COURT CASE

Johnson | FLORIDA SUPREME COURT CASE | 4/20/2017

"Petitioner pleaded guilty to armed burglary of a dwelling, armed kidnapping, attempted first-degree murder, and sexual battery using force or a weapon. Petitioner was sentenced to six concurrent life sentences. Petitioner’s sentences were based on offenses he committed when he was seventeen years old. After the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Graham v. Florida, the trial court set aside Petitioner’s life sentences and, after an evidentiary hearing, resentenced Petitioner to 100 years in prison for the first count and forty years on each remaining count, to run concurrently. The Fifth District Court of Appeal affirmed Petitioner’s sentence, concluding that Graham does not apply to term-of-years sentences. The Supreme Court quashed the decision of the Fifth District, holding that Petitioner’s 100-year sentence violates Graham and the Supreme Court’s decisions in Henry v. State and Kelsey v. State. Remanded."

"Accordingly, our focus has not been on the length of the sentence imposed, but the status of the offender and the possibility that he or she will be able to grow into a contributing member of society. In other words, although Graham focused on life sentences as applied to juveniles, in Henry, we applied Graham’s categorical rule as creating a special class of citizens, to wit: juvenile nonhomicide offenders."

-

Mosier | 10/13/17 | THE DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF FLORIDA SECOND DISTRICT

Mosier | THE DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF FLORIDA SECOND DISTRICT | 10/13/17

"[P]ursuant to Henry, we must consider three factors when reviewing a juvenile nonhomicide offender's term-of-years sentence. Post–Henry, we must ensure that a juvenile nonhomicide offender does not receive a sentence that provides for release only at the end of a sentence (e.g. a 45–year sentence with no provision for obtaining early release based on a demonstration of maturity and rehabilitation before the expiration of the imposed term, such as in Kelsey [v. State, 206 So. 3d 5 (Fla. 2016)]). Secondly, we must ensure that a juvenile nonhomicide offender who is sentenced post-Henry does not receive a sentence that includes early release that is not based on demonstration of rehabilitation and maturity (i.e. gain time or other programs designed to relieve prison overpopulation). Last, we must ensure that a juvenile nonhomicide offender who is sentenced post-Henry does not receive a sentence that provides for early release at a time beyond his or her natural life (e.g. a 1,000-year sentence that provides parole-eligibility after the offender serves 100 years). To qualify as a "meaningful opportunity for early release," a juvenile nonhomicide offender's sentence must meet each of the three parameters described in Henry."

-

Burrows | 3/3/2017 | DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL FLORIDA FIFTH DISTRICT

Burrows | 3/3/2017 | DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA FIFTH DISTRICT

"Jessy J. Burrows appeals his concurrent twenty-five-year sentences for his numerous non-homicide offenses committed when he was seventeen years old. The State properly concedes that Burrows is entitled to resentencing. See Kelsey v. State, 206 So. 3d 5, 8 (Fla. 2016) ("[A]ll juvenile offenders whose sentences meet the standard defined by the Legislature in chapter 2014–220, a sentence longer than twenty years, are entitled to judicial review."). Therefore, we reverse Burrows's sentences and remand for

resentencing under chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida.

REVERSED and REMANDED for Resentencing. "

-

Katwaroo | 2/2/2018 | District Court of Appeal of Florida, Fifth District.

Katwaroo | 2/2/2018 | District Court of Appeal of Florida, Fifth District.

"The defendant filed this rule 3.802 motion alleging that his sentence is illegal because, according to him, he was sixteen at the time he committed the offense. See Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460, 132 S.Ct. 2455, 183 L.Ed.2d 407 (2012) ; Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48, 130 S.Ct. 2011, 176 L.Ed.2d 825 (2010) ; Kelsey v. State, 206 So.3d 5 (Fla. 2016) ; Atwell v. State, 197 So.3d 1040 (Fla 2016). Procedurally, the defendant sought relief under the wrong rule because rule 3.802 applies only after a juvenile has been resentenced pursuant to section 921.1402, Florida Statutes, and the time for a review hearing has arrived.

Nevertheless, in light of his 30–year sentence, the defendant was entitled to receive judicial review of his sentence. See Burrows v. State, 219 So.3d 910 (Fla. 5th DCA 2017), but see Davis v. State, 214 So.3d 799 (Fla. 1st DCA 2017). However, it was error for the trial court to amend the sentence to provide for a review hearing without first conducting a resentencing hearing. Davis v. State, 230 So.3d 487 (Fla. 5th DCA 2017).

Accordingly, we reverse and remand for the trial court to treat the instant motion as a rule 3.800(a) motion and to hold a resentencing hearing pursuant to section 921.1402, Florida Statutes."

REVERSED and REMANDED.

Youth in Florida Courts | Variability, Inconsistency in Rulings

(2020 - current) = No reviews for All kids

-

PEDROZA | 2020 | Florida Supreme Court

"We hold that Pedroza has not established a Miller violation and, accordingly, is not entitled to relief. In so holding, we conclude that, to the extent this Court has previously instructed that resentencing is required for all juvenile offenders serving sentences longer than twenty years without the opportunity for early release based on judicial review, it did so in error.

B. Confusing and Erroneous Language in Henry , Kelsey , and Johnson

While the foregoing conclusions resolve the narrow issue presented in this case, we recognize that there has understandably been "considerable confusion" in the district courts of this state—caused largely by confusing language and dicta in our prior decisions—as to when a juvenile offender's term-of-years sentence requires resentencing under Miller or Graham . Hart , 246 So. 3d at 419 (addressing Graham ). This confusion stems from statements made in Henry , Kelsey , and Johnson regarding juvenile term-of-years sentences without a review mechanism that invoke the protections of Graham and Miller . We address the problematic statements in each of these cases— Henry , Kelsey , and Johnson —in turn."

-

GILCHRIST | 7-24-2020 | FLORIDA COURT OF APPEAL FIFTH DISTRICT

"In our original opinion, we held that it was error to modify a juvenile defendant’s sentence to allow for a review hearing without also holding a resentencing hearing under sections 775.082, 921.1401 and 921.1402, Florida Statutes.Gilchrist v. State, 277 So. 3d 638, 638-39 (Fla. 5th DCA 2019).However, the Florida Supreme Court quashed that decision and remanded with directions that we reconsider the matter in light of its recent decision in Pedroza v. State, 291 So. 3d 541 (Fla. 2020).Gilchrist v. State, No. SC19-613, 2020 WL 3790417, at *1 (Fla. July 7, 2020).In Pedroza, the supreme court held that resentencing is not required for juvenile offenders who are not serving a life sentence or its functional equivalent. 291 So. 3d at 549. Accordingly, we affirm the trial court’s order amending the sentences to provide for a review hearingand denying resentencing. We also affirm the denial of relief as to the eleven-year sentence imposed in Seminole County Circuit Court Case No. 06-CF-2921-Bwithout further discussion."

-

SANTIAGO | 8-28-2020 | FLORIDA COURT OF APPEAL FIFTH DISTRICT

"In our original opinion, we held that it was error for the postconviction court to modify Santiago’s sentence—i.e., providing for a review hearing—without also holding a resentencing hearing. Santiago v. State, 254 So. 3d 1125, 1126 (Fla. 5th DCA 2018). In doing so, we certified conflict with Pedroza v. State, 244 So. 3d 1128 (Fla. 4th DCA 2018).

Following the issuance of our opinion, we granted the State’s motion to recall and stay the mandate pending the Florida Supreme Court’s review of Pedroza. The Florida Supreme Court has now rendered a decision in Pedroza v. State, 291 So. 3d 541 (Fla. 2020), holding, among other things, that resentencing is not required for juvenile offenders unless they are serving a life sentence or its functional equivalent. 291 So. 3d at 549; cf. Gilchrist v. State, 44 Fla. L. Weekly D1787 (Fla. 5th DCA July 24, 2020)(interpreting Pedroza as so holding).

We determine that Santiago’s thirty-five-year sentence does not meet that standard. See Pedroza, 291 So. 3d at 548–49; accord Gilchrist, 44 Fla. L. Weekly D1787. Accordingly, we withdraw our previous opinion and substitute the instant opinion in its place. "

-

MELVIS | 10-14-2020 | DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF FLORIDA SECOND DISTRICT

"Applying the supreme court's decision in Pedroza to Mr. Melvis's arguments in this case, we must conclude that his thirty-year sentence is not unconstitutional under the holding in Graham because it is not a life sentence or the functional equivalent of a life sentence. Accordingly, he is not entitled to resentencing. We therefore affirm the postconviction court's order denying Mr. Melvis's amended motion to correct illegal sentence."

-

NUGENT | 05-11-2022 | Florida Court of Appeals, Second District

"Mr. Nugent's sentences are not illegal. Consequently, he is not entitled to resentencing.

The Florida Supreme Court recently clarified some "[c]onfusing and [e]rroneous language" in its prior juvenile sentencing jurisprudence. Pedroza v. State, 291 So. 3d 541, 546 (Fla. 2020). Pedroza established a simple rule: "[A] juvenile offender's sentence does not implicate Graham, and therefore Miller [v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460, 132 S.Ct. 2455, 183 L.Ed.2d 407 (2012) ], unless it meets the threshold requirement of being a life sentence or the functional equivalent of a life sentence." Pedroza , 291 So. 3d at 548. Mr. Nugent's sentences are neither."

FOR OVER A DECADE, FLORIDA COURTS HAVE REPEATEDLY URGED THE LEGISLATURE TO ADDRESS THE CRITICAL ISSUES IN §921.1402, HIGHLIGHTING AN URGENT NEED FOR CLARITY AND REFORM TO ENSURE JUSTICE AND FAIRNESS FOR YOUTH.

DETAILS.

We present below a compilation of pivotal cases that highlight the urgent need for legislative reform, noting specifically where courts have pointed out ambiguities, anomalies, and directly requested legislative guidance in their opinions.

The cases represent the interpretation of who deserves a chance at rehabilitation to the pressing constitutional concerns raised by the courts, each case underscores the statute's failure to uniformly protect the rights of juvenile offenders and the necessity for a clear, equitable legal framework.

It's important to note that while our list below is comprehensive, it does not encompass all cases of inequitable treatment but largely focuses on those where judicial commentary has explicitly called for legislative attention.

2015-2016 ▶

1) HENRY | FLORIDA SUPREME COURT [2015]

HENRYThe Florida Supreme Court clarified that the US Supreme Court's rulings on juvenile sentencing were not limited to life sentences, focusing on opportunities for juveniles to demonstrate maturity and rehabilitation.

“Thus, we believe that the Graham Court had no intention of limiting its new categorical rule to sentences denominated under the exclusive term of “life in prison.” Instead, we have determined that Graham applies to ensure that juvenile nonhomicide offenders will not be sentenced to terms of imprisonment without affording them a meaningful opportunity for early release based on a demonstration of maturity and rehabilitation.”

“the Eighth Amendment will not tolerate prison sentences that lack a review mechanism for evaluating [juvenile nonhomicide] offenders for demonstrable maturity and reform in the future . . . .”

2) ANTHONY DUWAYNE HORSLEY, JR., [MARCH 19, 2015]

HORLSEYSUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA NO. SC13-1938 NO. SC13-2000 [MARCH 19, 2015]

“This legislation, however, provided an effective date of July 1, 2014, leaving open the question of the proper remedy for those juvenile offenders, such as Horsley, whose sentences for crimes committed prior to July 1, 2014, violate Miller.”

“Indeed, although chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida, addresses the concerns of Miller moving forward, the legislation does not completely foreclose the arguments about the appropriate remedy under Miller because it provides only a prospective effective date. Therefore, it remains our task to determine what remedy should apply to those juveniles whose offenses were committed prior to the legislation’s July 1, 2014, effective date, but whose sentences remain unconstitutional under Miller.”

3) COLLINS | FLA. 1ST DCA [2016]

COLLINSCOLLINS V. STATE, 189 SO.3D 342, 345-46 (FLA. 1ST DCA 2016)

(BILBREY, J., specially concurring) Arguing that 921.1402(2)(d) and 775.082(3)(c) read together makes the review statute ambiguous as to who’s entitled to a review.

“I write with regard to the issue whether Appellant is entitled to the benefit of a review of his sentence for count 2 after 20 years pursuant to the revisions to sections 775.082(3)(c) and 921.1402(2)(d), Florida Statutes (2014), as provided by Chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida. Both the Appellant and the State raise the issue of sentence review in their briefs, but both parties seem to believe the availability of sentence review is tied to whether the term of years sentence is unconstitutional.”

“At the time Appellant was resentenced, the post-Graham revisions to sections 775.082 and 921.1402, Florida Statutes, were in effect, having become law as of July 1, 2014. Section 775.082(3)(c) provides for a review after 20 years per section 921.1402(2)(d) of “a person who is sentenced to a term of imprisonment of more than 20 years.” But section 921.1402(2)(d) applies to “a juvenile offender” and “juvenile offender” is defined in section 921.1402(1), as someone sentenced for an offense committed on or after July 1, 2014. Since Appellant was sentenced for a crime committed before July 1, 2014, a question arises as to whether he gets the benefit of the sentence review provided in section 921.1402(2)(d).”

“On the issue of statutory interpretation, the first determination is whether “person” under section 775.082(3)(c), Florida Statutes (2014), is more expansive than “juvenile offender” under section 921.1402(2)(d). If permitted to make this determination, I would hold that section 775.082(3)(c) should be applied to expand the class entitled to review under section 921.1402(2)(d). To hold otherwise would make the last sentence of section 775.082(3)(c) surplusage in violation of well[1]settled rules of statutory construction. See Hechtman v. Nations Title Ins. of New York, 840 So. 2d 993, 996 (Fla. 2003) (“[S]ignificance and effect must be given to every word, phrase, sentence, and part of the statute if possible.”). If the meaning of section 775.082(3)(c) were still thought to be ambiguous after applying other established rules of statutory construction, I would then apply the rule of lenity to Appellant and anyone resentenced under section 775.082(3)(c) pursuant to Graham, even if the resentencing was for an offense committed before July 1, 2014, so as to allow for the benefit of a sentence review under section 921.1402(2)(d). See § 775.021(1), Fla. Stat. (2014); Kasischke v. State, 991 So. 2d 803, 814 (Fla. 2008) (“[A]ny ambiguity or situation in which statutory language is susceptible to differing constructions must be resolved in favor of the person charged with an offense.”)."

“Furthermore, if the rules of statutory construction applied to sections 775.082(3)(c) and 921.1402 were unable to resolve the issue of whether Appellant is entitled to a sentence review, I would then look to Article I, Section 17 of the 10 Florida Constitution and the Eighth Amendment of the United States Constitution. I believe the constitutional requirements of Graham prohibit: [T]he state trial courts from sentencing juvenile nonhomicide offenders to prison terms that ensure these offenders will be imprisoned without obtaining a meaningful opportunity to obtain future early release during their natural lives based on their demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation. Henry, 175 So. 3d at 680 (emphasis added). The possibility of a few years of gain time accruing before the end of an offender’s life expectancy is not in my view a meaningful opportunity for early release as required by Graham. 3 In Henry the Florida Supreme Court unanimously stated: [W]e conclude that the Eighth Amendment will not tolerate prison sentences that lack a review mechanism for evaluating this special class of offenders for demonstrable maturity and reform in the future. 175 So. 3d at 680. I believe this statement mandates on Eighth Amendment grounds the application of section 921.1402(2)(d), even if my statutory interpretation concerns above are wrong."

“In Horsley v. State, 160 So. 3d 393, 405 (Fla. 2015), the Florida Supreme Court retroactively applied Chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida, “on all those juvenile offenders whose offenses were committed prior to that date but whose sentences are nevertheless unconstitutional under Miller.” It makes no sense to me that nonhomicide offenders would be entitled to less Eighth Amendment protection when resentenced under Graham than homicide offenders are when resentenced under Miller. See Kelsey, 183 So. 3d at 444-47 (Benton, J., dissenting).”

“Article I, Section 17 of the Florida Constitution requires us to construe the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment in conformity with the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution.”

“It should be emphasized that the only issue under consideration is a meaningful opportunity for early release, not entitlement to release. The trial courts are given broad discretion under section 921.1402(6), Florida Statutes, to consider “any factor” deemed appropriate. The opinion of a victim and the culpability of a defendant are among the factors that a trial court can consider. § 921.1402(6)(c) & (d), Fla. Stat.”

4) ANGELO ATWELL [2016] SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

ATWELL4) ANGELO ATWELL VS. STATE OF FLORIDA [MAY 26, 2016] SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA NO. SC14-193

This case challenged Florida’s parole system, stating that sentences mimicking life without parole, even if parole-eligible, are unconstitutional for juveniles. It emphasized the need for a review mechanism for juvenile nonhomicide offenders, highlighting the inadequacies of the current system under §921.1402.

5) JAMIE LYNN TYSON | FLA. 5TH DCA [SEPTEMBER 2, 2016]

TYSON5) JAMIE LYNN TYSON, CASE NO. 5D15-4050 FIFTH DISTRICT, SEPTEMBER 2, 2016

"Additionally, we certify the same four questions of great public importance that we did in Peterson:

1. DOES HENRY V. STATE, 175 So. 3d 675 (Fla. 2015), ONLY APPLY TO LENGTHY TERM–OF–YEARS SENTENCES THAT AMOUNT TO DE FACTO LIFE SENTENCES?

2. DOES HENRY APPLY RETROACTIVELY TO SENTENCES THAT WERE FINAL AT THE TIME HENRY WAS DECIDED?

3. IF HENRY ONLY APPLIES TO DE FACTO LIFE SENTENCES, THEN, IN DETERMINING WHETHER A TERM–OF–YEARS SENTENCE IS A DE FACTO LIFE SENTENCE, SHOULD FACTORS SUCH AS GENDER, RACE, SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS, AND POTENTIAL GAIN TIME BE CONSIDERED?

4. IF SO, AT WHAT POINT DOES A TERM–OF–YEARS SENTENCE BECOME A DE FACTO LIFE SENTENCE?"

6) ANTHONY MICHAEL ORTIZ | FLA. 1ST DCA [APRIL 4, 2016]

ORTIZ6) ANTHONY MICHAEL ORTIZ 1DCA CASE NO. 1D13-6229 APRIL 4, 2016.

“We recognize the anomaly that the Appellant will receive a sentence review under section 921.1402(2)(a), for his first degree murder conviction but not for home invasion robbery while armed with a firearm. Such is the current state of our precedent which we are bound to follow.”

7) THOMAS KELSEY [2016] SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

KELSEY7) THOMAS KELSEY, VS. STATE OF FLORIDA [DECEMBER 8, 2016] SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA NO. SC15-2079

This case extended judicial review to all juvenile offenders serving sentences longer than twenty years. It underscored the importance of providing juveniles with a meaningful opportunity for early release based on maturity and rehabilitation, which is not adequately addressed in §921.1402.

“We are thereby constrained to affirm in this case, but recognizing the need for clarity on this category of Graham cases certify the following question . . ..”

“For a period of nearly four years, the Florida Legislature left the trial courts and district courts of appeal to determine how to legally sentence juvenile nonhomicide offenders. In 2014, the Legislature passed chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida, which provided judicial review for juvenile offenders who were tried as adults and received more than twenty years of incarceration, with exceptions. Following that, this Court, in a unanimous decision, decided that juveniles who receive sentences that do not provide a meaningful opportunity for release are entitled to be resentenced pursuant to chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida"

“Accordingly, our focus has not been on the length of the sentence imposed but on the status of the offender and the possibility that he or she will be able to grow into a contributing member of society.”

“In other words, we have determined through our reading of the Legislature’s intent in passing chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida, that juveniles who are serving lengthy sentences are entitled to periodic judicial review to determine whether they can demonstrate maturation and rehabilitation.”

8) DAVIS | FLA. 4TH DCA [2016]

DAVIS8) DAVIS V. STATE, 199 SO.3D 546, 552 (FLA. 4TH DCA, 2016)

“We recognize continuing conflict among the district courts of this state on this issue. We thus certify several questions of great public importance with the hope that the Florida Supreme Court or the Legislature will act to bring more clarity and uniformity in this area of the law.”

“Based on the text of the respective statutes, our understanding of the 2014 legislation is that it was an attempt by the Legislature to comply with Miller through retroactive application in homicide cases (such as Thomas ), but that the changes to sentencing meant to comply with Graham were not intended to be retroactive in non-homicide cases (such as Peterson, Abrakata, and this case). Whether the differentiation was intentional is unclear.”

9) TARRAND V. STATE [9/2/2016] FLA. 5TH DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL

TARRAND9) TARRAND V. STATE (9/2/2016) FIFTH DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL

Held that juvenile homicide offenders who receive lengthy term-of-years sentences must be resentenced in light of new juvenile sentencing legislation. Applied Henry and Gridine principles to juvenile homicide offenders with lengthy term-of-years sentences, affirming their entitlement to resentencing.

“Admittedly, this case is different because it involves a homicide. Nonetheless, we believe our supreme court intends to apply the holdings of Henry and Gridine to juvenile homicide offenders who receive lengthy term-of-years sentences. We reach that conclusion based on the Florida Supreme Court's decision in Thomas v. State, 177 So.3d 1275 (Fla.2015), which quashed the underlying decision approving a juvenile homicide defendant's forty-year prison sentence. The supreme court ordered the juvenile to be resentenced in conformance with the 2014 juvenile sentencing statutes. Thus, we hold that while Tarrand's initial sentence was not prohibited under the Eighth Amendment, he must be resentenced in light of the new juvenile sentencing legislation now codified at sections 775.082, 921.1401 and 921.1402, Florida Statutes, to allow him a meaningful opportunity to obtain early release based upon demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation. REVERSED FOR RESENTENCING.”

2017 ▶

10) CLYDE EDWARD JOHNSON [2017] SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

JOHNSON10) CLYDE EDWARD JOHNSON, VS. STATE OF FLORIDA[4-2-2017] SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA NO. SC13-711

“In 2014, the Legislature passed chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida, which provided judicial review for juvenile offenders who were tried as adults and received more than 20 years’ incarceration, with exceptions. Later, this Court, in a unanimous decision, decided that juveniles who receive term-of-years sentences that do not provide a meaningful opportunity for early release based on maturity and rehabilitation during their natural lives are entitled to resentencing pursuant to chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida.”

“We conclude that reading these three cases together provides that that juvenile nonhomicide offenders are entitled to sentences that provide a meaningful opportunity for early release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation during their natural lifetimes and that gain time fails to meet those requirements.”

"Accordingly, our focus has not been on the length of the sentence imposed, but the status of the offender and the possibility that he or she will be able to grow into a contributing member of society. In other words, although Graham focused on life sentences as applied to juveniles, in Henry, we applied Graham’s categorical rule as creating a special class of citizens, to wit: juvenile nonhomicide offenders.”

“Accordingly, we determined that Graham was not limited to certain sentences, but rather was intended to ensure that “juvenile nonhomicide offenders will not be sentenced to terms of imprisonment without affording them a meaningful opportunity for early release based on a demonstration of maturity and rehabilitation.” Id."

“In light of this reasoning, we concluded that the Eighth Amendment, as read through Graham, requires a review mechanism for evaluating this class of offenders because “any term of imprisonment for a juvenile is qualitatively different than a comparable period of incarceration is for an adult.””

“Accordingly, we have determined that Graham prohibits juvenile nonhomicide offenders from serving lengthy terms of incarceration without any form of judicial review mechanism.”

11) ALFARO | FLA. 2ND DCA [12/27/2017]

ALFARO11) ALFARO V. STATE District Court of Appeal of Florida, Second District. (12/27/2017)

Clarified the application of Kelsey, affirming the entitlement to resentencing for juveniles sentenced to more than twenty years.

“The Supreme Court subsequently issued its decision in Kelsey v. State, 206 So.3d 5, 10 (Fla. 2016), expressly stating that term-of-year sentences do not have to constitute de facto life sentences in order for Graham to apply. Accordingly, we reverse the orders denying postconviction relief and remand for Alfaro to be resentenced as provided in Mosier.”

12) MONTGOMERY | FLA. 5TH DCA [2017]

MONTGOMERY12) MONTGOMERY V. STATE, 230 SO.3D 1256 (FLA. 5TH DCA, 2017)

“We review questions of statutory interpretation de novo. Patrick v. Hess, 212 So.3d 1039, 1041 (Fla. 2017). Our goal "is to determine legislative intent." Crews v. State, 183 So.3d 329, 332 (Fla. 2015). To do so, we begin with the plain meaning of the text of the statute. Diamond Aircraft Indus., Inc. v. Horowitch, 107 So.3d 362, 367 (Fla. 2013). "When the statute is clear and unambiguous, courts will not look behind the statute's plain language for legislative intent or resort to rules of statutory construction to ascertain intent." Daniels v. Fla. Dep't of Health, 898 So.2d 61, 64 (Fla. 2005). The statute's plain and ordinary meaning must control unless this leads to an unreasonable result or a result clearly contrary to legislative intent. Id.”

“Nevertheless, although I believe it was wrongly decided, I am bound by Burrows, and am now compelled to consider the remedy to which Appellant is entitled after demonstrating a violation of Graham. And although I cannot join all of the majority's reasoning, I agree with the majority's ultimate reading of sections 921.1402 and 775.087, which gives meaning to both statutes. That said, if the Legislature disagrees with our interpretation of these statutes, I believe it has every constitutional right to revise the statutes to clarify its intent.”

13) BURROWS V. STATE [3/3/2017] 5TH DCA

BURROWS13) BURROWS V. STATE (3/3/2017) FIFTH DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL

Recognized that juvenile offenders with sentences longer than twenty years are entitled to judicial review.

“The State properly concedes that Burrows is entitled to resentencing. See Kelsey v. State, 206 So. 3d 5, 8 (Fla. 2016) ("[A]ll juvenile offenders whose sentences meet the standard defined by the Legislature in chapter 2014–220, a sentence longer than twenty years, are entitled to judicial review."). Therefore, we reverse Burrows's sentences and remand for resentencing under chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida.”

14) MOSIER V. STATE [2017] FLA. 2ND DCA

MOSIER14) MOSIER V. STATE (2017) SECOND DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL

Highlighted the entitlement of a juvenile offender sentenced to thirty years' imprisonment for nonhomicide offenses to resentencing. Reversed a lower court's order and remanded for resentencing under juvenile sentencing guidelines.

“[P]ursuant to Henry, we must consider three factors when reviewing a juvenile nonhomicide offender's term-of-years sentence. Post–Henry, we must ensure that a juvenile nonhomicide offender does not receive a sentence that provides for release only at the end of a sentence (e.g. a 45– year sentence with no provision for obtaining early release based on a demonstration of maturity and rehabilitation before the expiration of the imposed term, such as in Kelsey [v. State, 206 So. 3d 5 (Fla. 2016)]). Secondly, we must ensure that a juvenile nonhomicide offender who is sentenced post-Henry does not receive a sentence which includes early release that is not based on a demonstration of rehabilitation and maturity (i.e. gain time or other programs designed to relieve prison overpopulation). Last, we must ensure that a juvenile nonhomicide offender who is sentenced post-Henry does not receive a sentence that provides for early release at a time beyond his or her natural life (e.g. a 1,000-year sentence that provides parole-eligibility after the offender serves 100 years). To qualify as a "meaningful opportunity for early release," a juvenile nonhomicide offender's sentence must meet each of the three parameters described in Henry.”

15) RICARDO MILLER [2017] FLA. 3RD DCA.

MILLER15) RICARDO MILLER V. STATE (2017) District Court of Appeal of Florida, Third District.

Affirmed the entitlement to judicial review and resentencing for all juveniles.

“Based on our reading of the applicable sentencing statutes and our recent decision in Neely v. State Nov. 30, 2016), all juveniles are entitled to judicial review and resentencing in accordance with the new statutes. Miller is thus entitled to judicial review and resentencing. The Third District applied this Court’s holding in Atwell to conclude that “all juveniles are entitled to judicial review and resentencing in accordance with the new statutes.”

2018 ▶

16) DANTE RASHAD MORRIS [2018] SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

MORRIS16) DANTE RASHAD MORRIS, VS. STATE OF FLORIDA [5-10-2018] SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA NO. SC16-2271

The State concedes that Morris is entitled to judicial review of his sentence, stating “if it is unclear that the new statute applied to Morris who was sentenced after its effective date for crimes committed before that date, this case should be remanded solely for the ministerial correction of his sentence to add the 20-year review provision.”

17) STATE V. PURDY | FLORIDA SUPREME COURT [8/30/2018]

PURDY17) STATE V. PURDY, FLORIDA SUPREME COURT, 8/30/2018

''We recognize that the scope of the existing statutory scheme has arisen in a context that is evolving.... and the fact that chapter 2014-220 was enacted prior to Henry, it is understandable that the Legislature would have crafted a statute dealing only with offenses that carry potential life sentences.''

“Because the plurality's analysis is one that the Legislature clearly did not contemplate or intend and is unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment, I dissent.”

"As a consequence of its interpretation of the statute, the plurality opinion correctly concedes that proportionality concerns may arise, stating "by limiting the review provisions to certain serious offenses, the Legislature has placed juveniles convicted of serious violent felonies in a better position than juveniles who commit less serious nonviolent offenses." Plurality op. at 729. However, a "sentence lacking any legitimate penological justification is by its nature disproportionate to the offense." Graham , 560 U.S. at 71, 130 S.Ct. 2011. When continued incarceration advances no penological purpose, the punishment runs afoul of the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. See id. at 59, 130 S.Ct. 2011 ("The concept of proportionality is central to the Eighth Amendment.").”

“It is an anomaly that Kenneth Purdy, who has proven to the courts of this State that he has moved past his previous crimes and is ready to be a contributing member of society, must continue to be imprisoned. That anomaly is unconstitutional. I would, instead, read the applicable statutes as the Fifth District Court of Appeal did—to require the trial court to review and allow it to modify a juvenile offender's aggregate sentence for multiple convictions arising out of the same criminal episode. I would thus answer the certified question in the affirmative and approve the result reached by the Fifth District. But, since the plurality decision does not reach that result, I urge the Legislature to review the unconstitutional incongruities demonstrated by this case.”

18) BUDRY MICHEL | SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA [JULY 12, 2018]

MICHEL18) BUDRY MICHEL SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA NO. SC16-2187 STATE OF FLORIDA, (JULY 12, 2018)

“5. I would strongly urge the Legislature to look at the implications of the plurality’s decision to determine whether amendments are warranted to chapter 2014-220, sections 2-3, Laws of Florida. See §§ 921.1401, 921.1402, Fla. Stat. (2018).”

19) BLOUNT V. STATE [2/28/2018] FLA. 2ND DCA

BLOUNT19) BLOUNT V. STATE (2/28/2018) SECOND DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL

Affirmed the entitlement to resentencing for a juvenile with forty-year concurrent sentences for nonhomicide offenses.

“Blount appeals an order denying his motion to correct illegal sentence under Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.800(a), in which he argued that he was entitled to resentencing with respect to his forty-year concurrent sentences for nonhomicide offenses that he committed when he was sixteen years old. The State correctly concedes that Mr. Blount is entitled to resentencing, and we reverse the order denying Mr. Blount's motion and remand for resentencing under the new juvenile sentencing guidelines in accordance with Johnson v. State, 215 So.3d 1237 (Fla. 2017), and Mosier v. State, 235 So.3d 957 (Fla. 2d DCA Oct. 13, 2017).”

20) CUEVAS V. STATE [2/14/2018] FLA 2ND DCA

CUEVAS20) CUEVAS V. STATE (2/14/2018) SECOND DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL

Discussed the resentencing of a juvenile offender sentenced to thirty years' imprisonment for nonhomicide offenses, affirming their entitlement to review.

“We note that the State recently conceded that a juvenile offender sentenced to thirty years' imprisonment for nonhomicide offenses was entitled to resentencing under Johnson and Kelsey. Mosier v. State, 42 Fla. L. Weekly D2181, D2181 (Fla. 2d DCA Oct. 13, 2017); accord Burrows v. State, 219 So. 3d 910, 911 (Fla. 5th DCA 2017) (noting that the State properly conceded that Burrows was entitled to resentencing and reversing his twenty-five-year sentences for nonhomicide offenses he committed as a juvenile and remanding for resentencing under chapter 14-220). Here, the State concedes that the sentences do not provide Cuevas with a meaningful opportunity for early release based on maturity and rehabilitation. Nevertheless, it argues that Johnson does not apply because Cuevas's sentences were imposed prior to Henry. We cannot agree with this interpretation of Kelsey and Johnson. Accordingly, we reverse the postconviction court's order and remand for Cuevas to be resentenced under chapter 14-220 as codified in sections 775.082, 921.1401, and 921.1402, Florida Statutes (2016). Reversed and remanded.”

21) KATWAROO V. STATE | FLA. 5TH DCA [2/2/2018]

KATWAROO21) KATWAROO V. STATE FIFTH DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL, 2/2/2018

Required resentencing for a defendant serving a 30-year sentence for second-degree murder committed as a juvenile.

“in light of his 30–year sentence, the defendant was entitled to receive judicial review of his sentence. See Burrows v. State, 219 So.3d 910 (Fla. 5th DCA 2017), but see Davis v. State, 214 So.3d 799 (Fla. 1st DCA 2017). However, it was error for the trial court to amend the sentence to provide for a review hearing without first conducting a resentencing hearing. Davis v. State, 230 So.3d 487 (Fla. 5th DCA 2017). Accordingly, we reverse and remand for the trial court to treat the instant motion as a rule 3.800(a) motion and to hold a resentencing hearing pursuant to section 921.1402, Florida Statutes.”

22) SANTIAGO V. STATE | FLA. 3RD DCA [8/8/2018]

SANTIAGO22) SANTIAGO V. STATE (2018) THIRD DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL, 8/8/2018

Initially granted a resentencing hearing, but following Pedroza, the court amended this ruling, affirming the original sentence and providing only for a review hearing.

“The court erred in so ruling because the constitutionality of a juvenile offender's lengthy term-of-years sentence is not solely dependent on whether a de facto life sentence has been imposed. See Peterson v. State, 193 So.3d 1034, 1038 (Fla. 5th DCA 2016), rev. denied, SC16-1211, 2017 WL 2705649 (Fla. June 23, 2017) (holding that a term-of-years sentence, which does not afford a non-homicide juvenile offender a meaningful opportunity for early release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation, violates the Eighth Amendment, requiring resentencing); accord Tarrand v. State, 199 So.3d 507 (Fla. 5th DCA 2016). We have also held that it is error to modify a juvenile defendant's sentence to allow for a review hearing without also holding a resentencing hearing. See Katwaroo v. State, 237 So.3d 446 (Fla. 5th DCA 2018). Accordingly, we affirm the trial court's ruling amending the sentencing documents to provide for a judicial review hearing, but reverse and remand for the court to conduct a full resentencing hearing. We also certify conflict with Pedroza v. State, 244 So.3d 1128 (Fla. 4th DCA 2018) which certified conflict with Katwaroo and Tarrand. AFFIRMED in part; REVERSED in part; and REMANDED with instructions. CONFLICT CERTIFIED.”

2019 ▶

23) WILLIAMS | FLA. 5TH DCA [2019]

WILLIAMS23) WILLIAMS V. STATE, 278 SO.3D 262, 267 (FLA. 5TH DCA, 2019)

Questioning whether the defendant could demonstrate ''that the legislature could not reasonably conclude that a juvenile offender'' who commits a non-homicide crime is being treated disparate by receiving a review at a later date than a juvenile that was principle to homicide.

“Instead, he argues that the trial court erred in finding the statutory interplay between sections 775.082(1)(b) 2 and 921.1402(2)(c) to be constitutional. Williams asserts that having his judicial review hearing and possible release to probation after fifteen years on his first-degree murder conviction, yet having to wait twenty years for his review hearing for his kidnapping conviction, results in "grossly disproportionate" sentences, in violation of his Eighth Amendment right to have his punishments "graduated and proportionate." See Graham v. Florida , 560 U.S. 48, 59, 130 S.Ct. 2011, 176 L.Ed.2d 825 (2010) ("Embodied in the Constitution's [Eighth Amendment] ban on cruel and unusual punishments is the ‘precept of justice that punishment for crime should be graduated and proportionate to [the] offense.’ ")“

“First, we observe that, to prove his claim that the sentences with the differing review hearings are grossly disproportionate, Williams would bear the difficult burden of demonstrating that the legislature could not reasonably conclude that a juvenile offender who personally kidnapped a victim should receive a later judicial review hearing than a juvenile offender who was a principal to first-degree felony murder but did not actually kill, intend to kill, or attempt to kill the victim. Nevertheless, because we find that we can effectively dispose of this case on other grounds, we decline to pass on the constitutionality of these statutes.”

2020 ▶

2020-Current: The Shift and Continued Struggle for Clarity

The year 2020 marked a turning point with the Pedroza v. State decision, which significantly narrowed the scope of juveniles eligible for sentencing reviews under §921.1402. This shift left many juveniles, particularly those with long-term term-of-years sentences, without the prospect of a review.

24) PEDROZA | FLORIDA SUPREME COURT [2020]

PEDROZA

PEDROZA24) PEDROZA V. STATE FLORIDA SUPREME COURT, 2020

The Florida Supreme Court (2020) decided that §921.1402 was intended only for offenders with life sentences, limiting the scope of juveniles eligible for sentencing reviews under §921.1402, marking a significant shift from previous rulings and excluding juveniles with long-term term-of-years sentences. Pedroza receded from and disapproved of several cases “to the extent they hold that resentencing is required for all juvenile offenders serving a sentence longer than twenty years without the opportunity for early release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.”

The court also receded from the test it had announced in Johnson, which set forth requirements for a juvenile's sentence to comply with the dictates of Graham. Id. at 548. The Johnson test stated that for a juvenile sentence to be constitutional under Graham, the juvenile must be given an opportunity for release before the end of the sentence, the opportunity must be based upon demonstrated rehabilitation and maturity, and the opportunity must be provided before the end of the juvenile's natural life.

"While the foregoing conclusions resolve the narrow issue presented in this case, we recognize that there has understandably been "considerable confusion" in the district courts of this state—caused largely by confusing language and dicta in our prior decisions—as to when a juvenile offender's term-of-years sentence requires resentencing under Miller or Graham. We hold that Pedroza has not established a Miller violation and, accordingly, is not entitled to relief. In so holding, we conclude that, to the extent this Court has previously instructed that resentencing is required for all juvenile offenders serving sentences longer than twenty years without the opportunity for early release based on judicial review, it did so in error.”

25) SHIVERS | FLA. 4TH DCA [2020]

SHIVERS25) SHIVERS V. STATE, 308 SO. 3D 176, 179 (FLA. 4TH DCA 2020)

Affirming one count of juvenile offender's sentence of twenty-five-years’ imprisonment for aggravated battery with a deadly weapon while masked because the sentence “does not, by itself, violate Graham or Miller.”

“he argues denying him review on this sentence would violate the Eighth Amendment and Equal Protection Clause. Although it is true that Shivers’s sentences result in an anomaly because he is not entitled to judicial review on the less severe first-degree felony, we reject his argument.”

26) RANCIFER BROWN | FLA. 3RD DCA [OCTOBER 28, 2020]

BROWN26) RANCIFER BROWN THIRD DCA, OCTOBER 28, 2020 NO. 3D19-1636 LOWER TRIBUNAL NO. 99-2559

"We recognize that “the ‘decisional path’ or ‘path of reasoning’ in Kelsey is less than clear,” Pedroza, 291 So. 3d at 548, and much of its rationale has been eroded by Pedroza. Nonetheless, Kelsey continues to compel the disposition of this case and others like it, which belong to a narrow and discrete class.”

27) MORALES | FLA. 2ND DCA [2020]

MORALES27) STATE V. MORALES, 299 SO. 3D 528, 529-30 (FLA. 2D DCA, 2020)

Morales was initially granted a resentencing hearing and resentenced to 20 years, the State appealed after Pedroza, and his sentence was then changed back to impose the original 30-year sentence.

“The State appeals the sentence imposed on resentencing after the trial court granted Juan Carlos Morales's motion pursuant to Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.800(a) to correct an illegal sentence. Based on then-governing precedent, the trial court correctly granted the motion. Nonetheless, based on Pedroza v. State, 291 So.3d 541 (Fla. 2020), which was decided while this appeal was pending, we must reverse. See Lowe v. Price, 437 So. 2d 142, 144 (Fla. 1983) ("Decisional law and rules in effect at the time an appeal is decided govern the case even if there has been a change since time of trial." (citing Wheeler v. State, 344 So. 2d 244 (Fla. 1977) ))”

28) ELIJAH DONCREEZE MACK | FLA. 2ND DCA [JULY 17, 2020]

MACK28) ELIJAH DONCREEZE MACK CASE NO. 2D18-3113 SECOND DCA (JULY 17, 2020)

“[B]ecause the statute limits the review provisions and does not deal with the overall sentence, there will be other cases, like this one, where the sentencing court is required to consider whether the offender "is rehabilitated and is reasonably believed to be fit to reenter society" even though the offender will continue to be incarcerated irrespective of the outcome of the hearing. Amicus points out that the continued incarceration of an offender on offenses arising from a single criminal episode under these circumstances— long after a judicial determination that the juvenile offender is rehabilitated—may raise additional Eighth Amendment issues.”

29) JONATHAN MELVIS [OCTOBER 14, 2020] 2ND DCA

MELVIS29) JONATHAN MELVIS (OCTOBER 14, 2020) SECOND DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL

“This case law included the Florida Supreme Court's decisions in Johnson v. State, 215 So. 3d 1237 (Fla. 2017); Kelsey v. State, 206 So. 3d 5 (Fla. 2016); Horsley v. State, 160 So. 3d 393 (Fla. 2015); and Henry v. State, 175 So. 3d 675 (Fla. 2015), as more fully discussed below. It also included this court's decisions in Cuevas v. State, 241 So. 3d 947 (Fla. 2d DCA 2018); Blount v. State, 238 So. 3d 913 (Fla. 2d DCA 2018); Alfaro v. State, 233 So. 3d 515 (Fla. 2d DCA 2017); and Mosier v. State, 235 So. 3d 957 (Fla. 2d DCA 2017), in which we found that sentences for terms of years similar to that imposed on Mr. Melvis were unconstitutional under the Florida Supreme Court's decisions interpreting Graham and that the defendants in those cases were entitled to resentencing under chapter 2014-220.”

30) JAKARIS TAYLOR [NOVEMBER 12, 2020] FLA. 4THDCA

TAYLOR30) JAKARIS TAYLOR, V. STATE OF FLORIDA. NO. 4D19-950 [NOVEMBER 12, 2020] FOURTH DCA

“The defendant again appealed, arguing the 2011 sentence was unconstitutional under Graham and the sentencing statutes because it constituted a de facto life sentence without the opportunity for parole. His appeals were consolidated. We affirmed the judgment and sentence but certified the following questions to the Supreme Court of Florida.

1. Does Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010), apply to lengthy term-of-years sentences that amount to de facto life sentences?

2. If so, at what point does a term-of-years sentence become a de facto life sentence? The supreme court quashed our decision and remanded for “resentencing in light of the decisions Henry v. State, 175 So. 3d 675 (Fla. 2015) and Gridine v. State, 175 So. 3d 672 (Fla. 2015).” Taylor v. State, 41 Fla. L. Weekly S453 (Fla. 2016).”

31) CHRISTINE LASHAY ROGERS | FLA. 1ST DCA [MAY 1, 2020]

ROGERS31) CHRISTINE LASHAY ROGERS, FIRST DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL FLORIDA NO. 1D19-878, MAY 1, 2020

“BILBREY, J., concurring. Under our holding today, offenders like Rogers will not get the benefit of a possible reduced sentence upon resentencing or a sentence review hearing merely because the offender chose to file the motion under rule 3.800 instead of rule 3.850. I believe the majority’s interpretation of rule 3.800 is correct, but I also believe the disparate treatment of offenders, who at one time were thought to have an unconstitutional sentence, based only on how they styled the motion bears mentioning.”

“All this aside, the most significant point is that the district courts—though in conflict on the jurisdictional issue—all arrive at the same destination on the ultimate question of practical importance: what must a trial court do when presented with a change in the law at the time of resentencing? Neither line of jurisdictional precedent stands in the way of a trial court applying the legal standards prevailing at the time of actual resentencing (versus the time of the order granting entitlement to resentencing). An order granting entitlement to resentencing, whether a final order or not, doesn’t bar a resentencing court from applying the prevailing law at the time when resentencing actually occurs; interpreting Simmons as such a bar, for example, is mistaken.”

32) DARRYL LEN MORGAN | SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA [OCTOBER 28, 2020]

MORGAN32) DARRYL LEN MORGAN, PETITIONER, V. STATE OF FLORIDA, RESPONDENT. SC20-641 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA ON PETITION FOR DISCRETIONARY REVIEW FROM THE SECOND DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL DCA NO. 2D18-4940 [OCTOBER 28, 2020]

State, ANSWER BRIEF ON THE MERITS. Discusses how Morgan was granted a resentencing hearing, but then case law changed before he was resentenced, resulting in him then being denied.

“from 2016 until 2018, Atwell was the law of Florida. During that span hundreds of juvenile homicide offenders moved for resentencing under Rule 3.800(a), arguing that—as retroactively applied to them—Miller and Atwell rendered their life-with-parole sentences illegal. Trial judges uniformly granted those defendants relief, deeming their sentences unconstitutional and scheduling resentencing hearings.”

“Petitioner was granted resentencing only because of this Court’s decision in Atwell, which proved to be a momentary aberration in Eighth Amendment juvenile sentencing jurisprudence.”

33) DEON CORNELL GILCHRIST [7/24/2020] FLA. 5TH DISTRICT

GILCHRIST33) DEON CORNELL GILCHRIST (7/24/2020) FIFTH DISTRICT

Appealed the partial denial of his motion to correct his sentence, reflecting the complexities in applying resentencing and review mechanisms for juvenile offenders.

“In our original opinion, we held that it was error to modify a juvenile defendant's sentence to allow for a review hearing without also holding a resentencing hearing under sections 775.082, 921.1401 and 921.1402, Florida Statutes. Gilchrist v. State, 277 So. 3d 638, 638-39 (Fla. 5th DCA 2019). However, the Florida Supreme Court quashed that decision and remanded with directions that we reconsider the matter in light of its recent decision in Pedroza v. State, 291 So. 3d 541 (Fla. 2020). Gilchrist v. State, No. SC19-613, 2020 WL 3790417, at *1 (Fla. July 7, 2020). In Pedroza, the Supreme Court held that resentencing is not required for juvenile offenders who are not serving a life sentence or its functional equivalent. 291 So. 3d at 549. Accordingly, we affirm the trial court's order amending the sentences to provide for a review hearing and denying resentencing. We also affirm the denial of relief as to the eleven-year sentence imposed in Seminole County Circuit Court Case No. 06-CF-2921-B without further discussion.”

34) HART V. STATE [12/31/2020] FLA. 1ST DCA

HART34) HART V. STATE (12/31/2020) District Court of Appeal of Florida, First District.

Hart's aggregate 50-year prison sentence for crimes committed as a juvenile was affirmed as it did not violate Graham or Miller because it was not a life sentence or the equivalent.

2021 ▶

35) MICHAUD | 2ND DCA [APRIL 16, 2021]

MICHAUD35) MICHAUD V. STATE (2021) CASE NO. 2D20-1287 (2DCA APRIL 16, 2021)

This case discusses holdings on who qualifies for relief, particularly for those that have life with parole. Michaud's appeal for relief under section 921.1402 was denied as his offense occurred before July 1, 2014, and his sentence was deemed constitutional.

“This statute has been held to apply retroactively to "all juvenile offenders whose sentences are unconstitutional under Miller, even if the juvenile's offense was committed prior to the July 1, 2014, effective date of the legislation." Falcon v. State, 162 So. 3d 954, 963 (Fla. 2015), receded from on other grounds by Williams v. State, 242 So. 3d 280 (Fla. 2018). This does not include Michaud, whose offense occurred prior to July 1, 2014, and whose sentence has been determined to be constitutional. See Michel, 257 So. 3d at 4 (holding that "juvenile offenders' sentences of life with the possibility of parole after 25 years do not violate the Eighth Amendment of the United States Constitution as delineated by the United States Supreme Court" in Miller/Graham and that "[t]herefore, such juvenile offenders are not entitled to resentencing under section 921.1402"

“Michaud is not entitled to relief under section 921.1402 because his offense occurred prior to July 1, 2014, and his sentence is constitutional, see Michel, 257 So. 3d at 4, and the circuit court departed from the essential requirements of law in granting his rule 3.802 motion.”

36) BELL | 1ST DCA [2/22/2021]

BELL36) BELL V. STATE FIRST DCA, NO. 1D19-1542, 2/22/2021

This case discussed the “aftermath of the Graham and Miller decisions” and the enactment of §921.1402. The court's deliberations shed light on the challenges posed by the statute's language, especially in terms of its application to different categories of juvenile offenders.

37) TYREE WASHINGTON [AUGUST 31, 2021] 1ST DCA

WASHINGTON37) TYREE WASHINGTON NO. 1D19-4487 AUGUST 31, 2021, FIRST DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL FLORIDA

“The net effect of Jones is that clarification about the process and standards for discretionary juvenile sentencing decisions must come from developments in state procedures and legislation, which in Florida originate in our supreme court and the legislature. In conclusion, denial of the motion for clarification is proper because an intermediate appellate court cannot practically provide clarity beyond the cases it is presented. See, e.g., J.M.H. v. State, 311 So. 3d 903, 913 (Fla. 2d DCA 2020) (explaining why an abuse of sentencing discretion existed in that particular case). As reflected in Jones, our disposition today is not the last word on juvenile sentencing reforms and policies, which belong to those who may act on them, such as the legislature, the Governor and cabinet, and our supreme court.”

“These facts are relevant to “[t]he defendant’s age, maturity, intellectual capacity, and mental and emotional health at the time of the offense,” § 921.1401(2)(c), Fla. Stat., “[t]he defendant’s background, including his or her family, home, and community environment,” id. at (2)(d), “[t]he nature and extent of the defendant’s prior criminal history,” 7 with this conclusion because, with an abuse of discretion standard of review, it is not enough to disagree. In order to reverse the trial court’s judgment, it must be that no “reasonable [judge] could differ as to the propriety of” the sentence. Canakaris v. Canakaris, 382 So. 2d 1197, 1203 (Fla. 1980). Here, I find that reasonable judges could differ.”

38) CORBETT | 4TH DCA [JANUARY 06, 2021]

CORBETT38) CORBETT V. STATE (2021) NO. 4D18-1654 4DCA JANUARY 06, 2021

This case discussed the application of Pedroza to a 30-year prison sentence for a nonhomicide offense.

“The Florida Supreme Court quashed this Court's decision in Corbett v. State, 253 So. 3d 603 (Fla. 4th DCA 2018), and remanded for reconsideration and application of Pedroza v. State, 291 So. 3d 541 (Fla. 2020). We affirm. Under Pedroza, Appellant's 30-year prison sentence for a non-homicide offense is not the functional equivalent of a life sentence, and Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48, 74, 130 S.Ct. 2011, 176 L.Ed.2d 825 (2010), and Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460, 132 S.Ct. 2455, 183 L.Ed.2d 407 (2012) are not implicated.”

39) MARK AGENOR [October 13, 2021] 2ND DCA

AGENOR39) MARK AGENOR v. STATE OF FLORIDA, Appellee. No. 2D20-3052 (October 13, 2021) DCA SECOND DISTRICT

Agenor's offenses were committed in 2015, after the effective date of July 1, 2014, in §921.1402.

“In turn, sections 775.082(3)(c) and 921.1402(2)(d) provide that a person under the age of eighteen, who commits any felony punishable by life (other than those listed in the murder statute, section 784.02) and who is sentenced to a term of more than twenty years, is entitled to a review of that sentence after the first twenty years are served. See also Graham v. State, 286 So. 3d 800, 803 (Fla. 1st DCA 2019) (explaining the different classifications of offenses eligible for review under section 921.1402). Clearly, Agenor's conviction and twenty-five-year sentence on count III qualify for a twenty-year review. Therefore, we reverse the order on appeal as to count III of case number 2015-CF-7225.”

40) ELLIS JAREL MCARTHUR | 1ST DCA

MCARTHUR40) ELLIS JAREL MCARTHUR FIRST DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL STATE OF FLORIDA No. 1D19-403 2021

“I write to highlight that this is again a case in which Appellant will be treated differently than other “defendants who committed serious criminal offenses as juveniles.” Rogers v. State, 296 So. 3d 500, 519 (Fla. 1st DCA 2020) (en banc) (Bilbrey, J., concurring). Had Appellant been sentenced before the State withdrew its initial concession, he faced the prospect of receiving a shorter sentence as well as the assurance of a future sentence review hearing to again provide an opportunity to reduce the sentence.”

“Juvenile offenders in various courts throughout the State with similar sentences to Appellant were no doubt resentenced under chapter 2014-220, Laws of Florida, before the Florida Supreme Court resolved the conflict among the districts in Pedroza II.5 A possible fix for this disparate treatment of juvenile offenders may be for the Legislature to extend the benefit of chapter 2014-220 to all juvenile offenders serving long term of year sentences regardless of whether their sentences were now found to violate the Eighth Amendment as stated in Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010), or Miller. Another possible fix may be the revival of parole for certain juvenile offenders. See, e.g., Washington v. State, 103 So. 3d 917, 921 (Fla. 1st DCA 2012) (Wolf, J., concurring) (“Our Legislature has repeatedly, arguably unwisely, eschewed the alternative of parole.”). A final possible fix could be the use of the clemency process. See Art. IV, § 8, Fla. Const. Either of the first two potential solutions would likely be available to the Legislature following the amendment to the Savings Clause in article X, section 9 of the Florida Constitution. See Jimenez v. Jones, 261 So. 3d 502, 504 (Fla. 2018) (noting that the amendment means “that there will no longer be any provision in the Florida Constitution that would prohibit the Legislature from applying an amended criminal statute retroactively”)”

“There would be no guarantee of early release, and some or even many juvenile offenders serving long sentences could be found unsuitable for it. Rather, Appellant and other similarly situated juvenile offenders with long but constitutional term of years sentences would be afforded at least “some meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation,” Graham, 560 U.S. at 75, which is lacking under the current state of the law.”

“This likely includes not only juvenile offenders convicted of murder like Appellant but also juvenile offenders convicted of lesser, but still serious felonies.”

2022 ▶

41) DARRYL LEN MORGAN [11/3/2022] Supreme Court of Florida No. SC20-641

MORGAN41) DARRYL LEN MORGAN (11/3/2022) Supreme Court of Florida No. SC20-641

Determined that Morgan's life with the possibility of parole sentence does not necessitate resentencing.

“held that orders granting relief under rule 3.800(a) are “not final or appealable until resentencing has occurred”

42) CLARENCE FREEMAN | 1ST DCA [3/9/2022]

FREEMAN42) CLARENCE FREEMAN FIRST DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL No. 1D21-3274, 3/9/2022

Determined that Freeman is not entitled to judicial review of his sentence.

“Freeman received a thirty-five-year sentence. This sentence does not “meet the threshold requirement of being a life sentence or the functional equivalent of a life sentence.” See Pedroza v. State, 291 So. 3d 541, 548 (Fla. 2020) (holding that a forty-year sentence is not the functional equivalent of a life sentence). For these reasons, Freeman is not entitled to judicial review of his sentence under rule 3.802 or section 921.1402.”

2023 ▶

43) ROBERT D. GARNER [SEPTEMBER 15, 2023] 2ND DCA

GARNER43) ROBERT D. GARNER, APPELLANT, V. STATE OF FLORIDA, APPELLEE. NO. 2D22-866 SEPTEMBER 15, 2023 2DCA

“Therefore, until such time that the United States Supreme Court or the Florida Supreme Court holds, or the Legislature enacts law, that precludes the imposition of consecutive life sentences—even with the possibility of parole or judicial review after twenty-five years for each sentence—for juvenile homicide offenders who commit multiple murders, we are bound to follow Graham, Miller, Michel, and Franklin.”

“But if Mr. Garner is eventually granted release on parole on his first sentence, an issue that will need to be resolved is whether there will still be a penological purpose justifying his return to prison to begin serving his second sentence, for which he would not be eligible for release on parole for twenty-five years. Current law does not clearly resolve this issue when the sentences are for multiple homicides. The Florida Supreme Court has reiterated that an offender's juvenile status implicates the Eighth Amendment and warrants different considerations when the offender faces criminal punishment as if the juvenile were an adult.”

44) JEFFREY MURPHY [JULY 26, 2023] 2ND DCA

MURPHY44) JEFFREY MURPHY V. STATE OF FLORIDA, APPELLEE. NO. 2D22-642 JULY 26, 2023 DCA SECOND DISTRICT